23-minute listen/watch | 14-minute read | 1-minute teaser

The Earth can shift suddenly, with sinkholes and landslides posing serious risks to people and property. Scientists are now using existing fiber optic cables in cities to detect potential geohazards before they strike. This innovative approach is expanding to monitor flooding and even track human movement, unlocking new possibilities for data collection and understanding our world.

Transcript

Tieyuan Zhu

This technology can collect the real-time data. This real-time data really can give you the clue about what happened between today and then the day in next year because they really capture everything they have. And then you can, using this data, really improve our understanding of all this physical cause of this change.

Host

Welcome to Growing Impact, a podcast by the Institute of Energy and the Environment at Penn State. Each month, Growing Impact explores the projects of Penn State researchers who are solving some of the world's most challenging energy and environmental issues. Each project has been funded by the institute's seed grant program that grows new research ideas into impactful energy and environmental solutions. I'm your host, Kevin Sliman.

The Earth can shift and move in a moment. Sinkholes and landslides can occur without warning, causing damage to property and injury or death to those in the area. But what if there was a way to recognize the danger before it struck? In this episode of Growing Impact, we look back on a seed grant project from 2019 that uses fiber optic cable to identify potential geohazards.

As the project continues to grow, it's finding new opportunities to collect and analyze data in amazing ways, like on flooding and even the movement of people. And it's all thanks to an innovative idea to use fiber optic cables that are already buried in the ground below us.

Tieyuan Zhu

Hi, Kevin. How are you?

Host

Good. How are you?

Tieyuan Zhu

Yeah, I'm doing good, doing good.

Host

Thanks so much for talking through this. We really wanted to visit some of these older seed grants, and I think, I mean, your project is just a great example of something that got legs and has really moved forward. I'm just interested in learning more about it. So thanks so much for taking time to do this. Can we start with you introducing yourself?

Tieyuan Zhu

Oh, thank you, Kevin. I'd be very glad to be with you today. So I'm Tieyuan Zhu from the Geosciences Department. I'm an associate professor. I'm interested in, you know, how our Earth's near-surface be modified by external impact, for example, the short-term climate change. You know, how does that impact our Earth's near-surface? I'm basically using geophysics tools, theory, and method to understand the physical cost of these changes.

With that, we can understand what caused the geohazards, you know, for example, sinkholes collapse and what caused that water to, you know, go from the surface to the to the deep Earth. Why’d that happen? What's the physical, you know, ... of that? So that's my primary interest.

Host

The seed grant project that you applied for years ago really took off. It focused on using fiber optic cables, like the ones used to provide internet access, for seismic monitoring, and to improve hazard assessment. Can you talk us through that? Talk about the, you know, how (a) you even thought that... could fiber optic cables be used in this way? And then just kind of talk us through a little bit of the science and help us understand it.

Tieyuan Zhu

The fiber optic cable sensing using the fiber optic cable is, very new, you know, research front in geophysics. Back to I think, ten years ago, the oil and gas industry started to look at this new technology, to see if that works for oil and gas wells because it's very difficult to put the sensor, conventional sensor in the wells because the well has so limited of space. So this technology basically can detect a very small change in the anywhere the cable can access. It's very easy to actually put the cable down to the borehole versus conventional sensors because sensors is always have certain volume. But this cable is just as thin as your hair. So it's easy to attach with a casing and then lower to the very deep borehole.

So that's the original, you know, idea, kind of born in geophysics community. And then back to five years ago, you know, when I initialized my research, I'm just asking, oh, you know, can we use, you know, existing cable, for example, that already been deployed in city for telecommunication purposes? Can we use that for geophysical research? Instead of going through the borehole, can we just do you know a pipeline in, you know, conventional city infrastructure?

The big reason is in our urban city, it's very difficult to put a conventional sensor in subsurface. There are lots of issues with permits, there are lots of issues with security.

And also it's too costly to put the conventional sensor everywhere across the one street block. But the cable, it is everywhere already deployed in the pipeline. Telecommunication industry already spent you know, billion dollars to put that everywhere in our city. So that's kind of the idea, if we can combine, you know, existing infrastructure for, you know, geophysics sensing research, then I begin to, you know, at that time, I see this is going to be a great deal for us and also great deal for research in urban cities.

Host

Can you talk a little bit about the science behind it? So you have all this existing cable throughout cities and under streets. How then do you utilize that and what other things do you need to do to actually gather that information? Can you talk a little bit about that?

Tieyuan Zhu

The telecom fiber optic cable is basically made of glass. But if you look at using microscope, there are lots of little, you know, we call them scatter, impurities in the glass in the nanometer scale. Okay. So when you're sending the laser through the cable, the telecom message basically passes through from State College (Pennsylvania) to New York.

But there, you know, only 5% or 10% energy actually backscatter back to your sending place. For geophysics, if we send something to location A, we really want to know how far is that location to us. If we know that information... so if something happened at the location A, we can know where that happened. So the basic principle is going to be, you send a laser to the glass, through the glass, and then energy is going to kick back. And then we are going to analyze this laser energy to understand where that something happened, at a which location, and how much that magnitude is based on the laser power.

Host

Interesting. So if nothing is happening, you get kind of a baseline reading. But if something happens, you then start getting more kickback or feedback. I guess of some sort...

Tieyuan Zhu

Exactly.

Host

OK.

Tieyuan Zhu

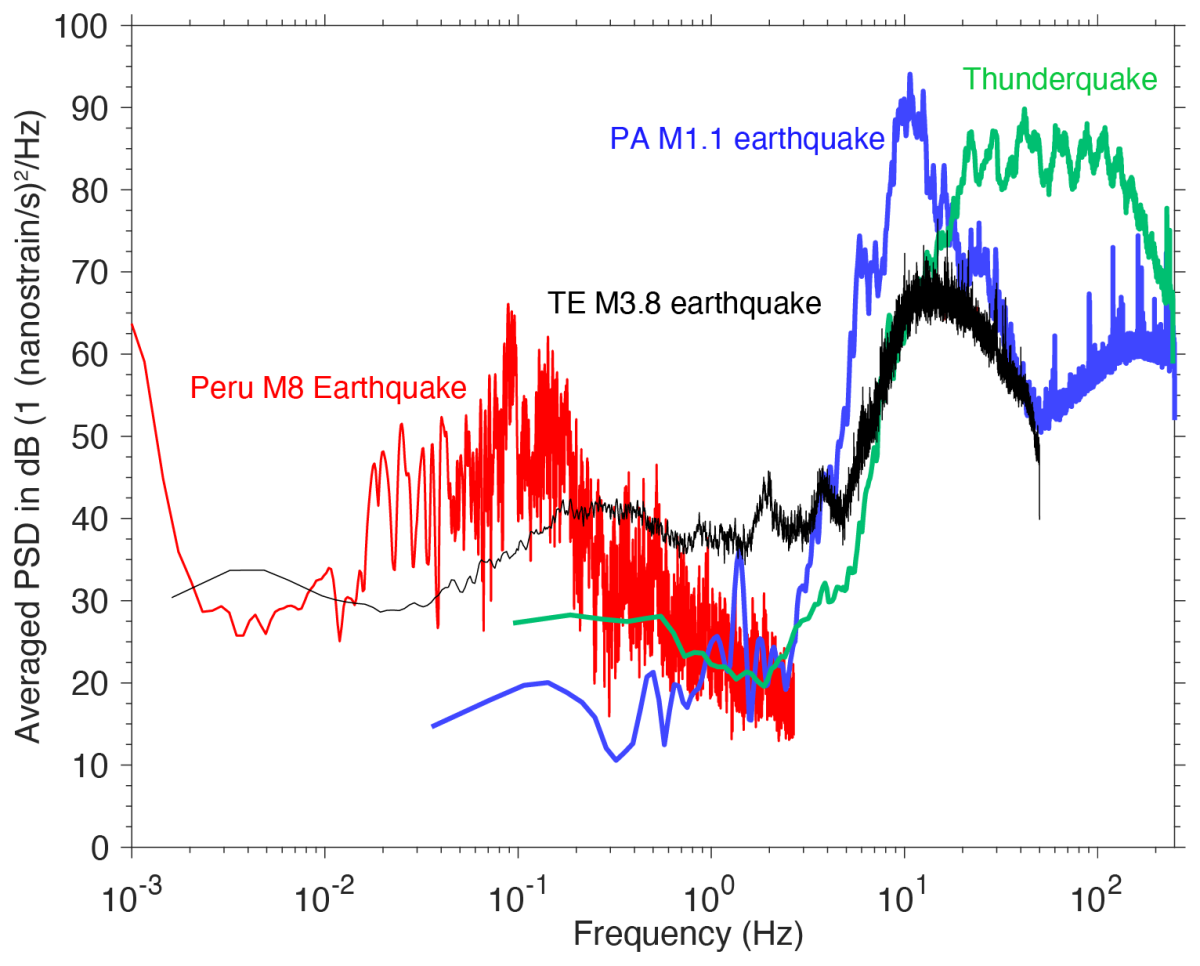

For example, I can give you a simple example. For example, if an earthquake happens, the earthquake is going to shake the ground. When you shake the ground, that is going to modify the fiberoptic lens, for example. We call this “strain.” If that strain is modified, we can detect how much, you know, the lens is modified. So we know where that is modified.

And then what...how much of the strain over there? So that tells us when the earthquake hits this area, how much damage you can receive. So that's very key information because we always want to understand, oh, with an earthquake, something happened, how much damage you can expect at a particular location.

Host

Wow. That's amazing that you can calculate that much from the feedback that you're getting. Well, that kind of brings us to the next question. So you mentioned earthquakes, what other sorts of seismic hazard or happenings or geological events maybe can be detected?

Tieyuan Zhu

Because we know the geophysics principle of this technology is so cool, we can detect some damage at a particular location. But what else, you know, signal we can record? So that's actually our first question in our proposal. And then you know, we started data recording back to, you know, 2019. And we actually saw lots of amazing things.

For example, the first signal we saw was from a thunderstorm. The underground cable, you can listen to a thunderstorm, you know, the lightning and thunder across State College (Pennsylvania). We see a beautiful, you know, movement across State College. That's never been achieved in meteorology community. It’s because their radar sensors, or their meteorology sensors, are two kilometers away. For example, across the whole of State College, they only have one or two. So for example, that's kind of like severe weather information.

The second, a new signal we discover from our data is the flooding information. When the severe weather puts lots of water on the ground, you know, people always want to know all where are the, you know, flooding-prone areas.

Right. And we look at the cable, the water is going to pour into the sewer. So that actually generates a strong energy in our cable. We saw that energy. And then, what do we do is we analyze, oh, how big is our rain? You know, from the weather station we know how big is our rain. And as a way compare our data energy and as we do the, we call the cross-correlation. And then we analyze, oh, in this particular rain or precipitation corresponds to this kind of energy. And then we can understand, oh, using our data to understand how much water you're going to put on the ground.

The recent one, you know, my student is just working on the manuscript, is we look at the potential of sinkholes because we found the using the cable, you know, in total is about 4.2km long. So with that information, we actually can image the whole subsurface along the cable. And then we analyze our results to see some potential -- we call this a low-velocity zone. So that's a low-seismic velocity because you do have a cavity compared to you have limestone rock. So rocks propagate a seismic velocity faster compared to air if that’s a cavity.

So we actually can detect that low-velocity zone. So that tells us oh here is a potential cavity. And then if you go to the surface you look at that soil thickness, you can tell, oh this is a potential, you know, sinkhole development area. At the beginning, we don't know all the hazards we can detect.

But you know when we're looking into the data, we found there’s a lot of potential to help us to, you know, really, detect these geohazards.

Host

Does your technology offer early detection that can provide a community with time to respond before an event occurs?

Tieyuan Zhu

I totally think so. I just gave you one example about the sinkholes, potential sinkholes. This is because, as I said, the technology can help us to image the subsurface velocity structure. If we can identify the more cavity under a particular location, this cavity information in the, you know, certain depth is really the key to protecting this collapse. So that is kind of my understanding how, you know, this knowledge we study, we ... using our data to help the geohazard prevention.

Host

Could you talk a little bit about what the inspiration was to using fiber optics in this manner?

Tieyuan Zhu

So when geophysicists start to use fiber optic cable, they always use a new fiber optic cable. So that means, oh, we purchase the new cable from the telecom, you know, manufacturer and then we deploy it somewhere for geophysics monitoring. But our research is really taking advantage of what we call the dark fiber. So the fibers are used for telecommunication but is already deployed in our cities.

Host

You're taking advantage of what you're calling dark cable. So these are ones that are not being used for telecom purposes currently, but they're deployed, but they're not being used?

Tieyuan Zhu

The 10% of the fiber optic cable is I use -- this cable is used for backup. If there is anything emergency happens, they’re going to switch the cable. That doesn’t disturb our phone call, our internet because they do have some backup cables over there. Because that luckily because I have 10%, that's why we do have lots of dark fiber underground, you know, prevalence. If that, you know, only, let's say 1%, 0.5% can be used for geophysical research that already, you know, a big deal for geohazardous monitoring incidents.

Host

Where are some places where this monitoring system has been utilized, and can you share some success stories around it?

Tieyuan Zhu

So far, we did experiments in State College since 2019. We also got supported from NSF City Program to demonstrate this technology in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. So we also want to replicate, you know, the research in a larger scale city. Can we really observe something similar signals in Pittsburgh? Can we really see the flooding signals over there? Can we see the landslide signals? Can we also detect the cavity sinkholes in Pittsburgh? So that's kind of the research question we are trying to answer in a larger scale, you know, experiment.

Host

Could you talk a little bit, who are some of the groups that could benefit from this technology?

Tieyuan Zhu

I can imagine many of you know, city you know, planner or management groups can benefit the technology in terms of city geohazard prevention. For example, the Water Authority, they can use our information to determine the flooding zones in a city. For, you know, geophysics community, I think our study also can benefit other people's research because we published our, you know, research discoveries about these geohazards, I believe, you know, in the next few years or decades, if the similar, you know, if other cities, for example, have similar geohazard issues, they can look at, because, again, the fiber optic cable is everywhere in our cities. This is not that difficult to replicate in another place.

Host

So this research, do you consider this an open source, kind of like, a giving back to the community so that, you know, others can benefit from this technology. Once that's created, is that something that you're looking like, yeah, now other communities take advantage of this to benefit your community?

Tieyuan Zhu

For sure. I think two ways: One is benefits to our community by sharing the data, sharing the research results, and, you know, talk to colleagues and let them know the lessons we learned, you know, from this project. And also this can benefit other communities. For example, you know, when we look at the flooding, you know, signals, we actually want to gather information from engineering because they really design the sewer system.

We want to get, you know, information about, how, you know, how big is their sewer hole, you know, how deep. This information helps us to calculate how much water got into there. So that information actually also helps us to calibrate our signals. And I think these are kind of like a mutual benefits to different communities because I believe our data is also useful for engineering people to really design some appropriate, you know, sewer in the future if they build a new city.

But at the same time, you know, we're using their information as a kind of like a grounded truth or some information that really calibrated our data. Because our data is again a matter of strength. It’s a geophysics or physics unit. It’s not a water unit. If you want to use that for the water, you really want to do the, you know, very accurate calibration, and that can serve the data community using geophysics data to solve the water issue.

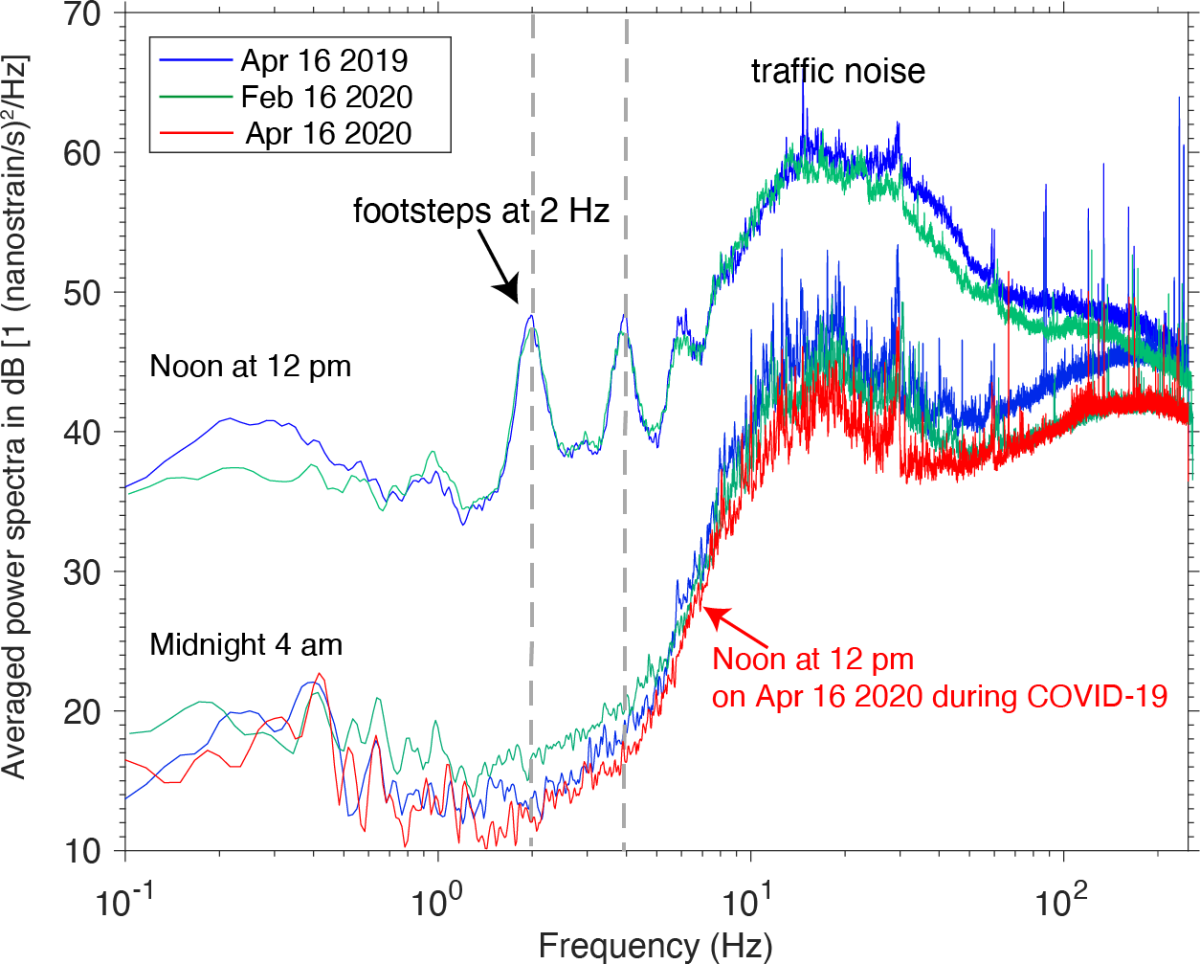

And what exciting discovery is using our, we call the noise data, to understand the human mobility during the Covid 19. So when we look at the data during the Covid in 2020, we actually found the data, we call the noise level, is very low compared to a few months ago in 2019. But when we really look into when that a noise level really change, we found the in State College is about, you know, March 15, 2020.

That's exactly the spring break when we are here in 2020. And then we look at even after spring break the noise level still stayed very, very low. And then we realize, oh it’s because of Covid. So the University actually shut down after this spring break. Students all won't come back to the, you know, University Park campus. And that kind of helps us to see, oh, our data really can also help to understand the human mobility in the city area.

Host

Could you talk a little bit about how the early support from IEE enabled success in this project?

Tieyuan Zhu

You know, I really appreciate you know, how the IEE seed grant can help junior faculty initialize some new ideas. Back to 2019, you know, when I received the IEE seed grant, it really helped me purchase the equipment, and then once we got our equipment, you know, we can have data collection. Without this new, you know, equipment, we just cannot get any data collection. IEE really provided that, you know, resources to me. Even now, we actually use that equipment for the Pittsburgh project.

Host

How is this project evolved since getting the IEE seed grant?

Tieyuan Zhu

Luckily, we got a big project from the NSF Signals in the Soil. That's a $1.2 million project. So that actually helped us to set up a new project in Alaska to understand actually permafrost degradation. So we, you know, we deploy that fiber optic cables in Barrow, Alaska. It’s about a two kilometers long. And, we collect the data even until now, we already collected three years of data.

So we saw lots of, you know, interesting signals about the permafrost degradation, about, in particular, the ice ... cracking, and also, the iceberg, you know, break on the ocean floor. So that's kind of amazing, you know, research direction, you know, I'm working on now. But if we think about, how this, you know, project evolved, it’s really with, you know, big support from IEE.

And then we do get the equipment and then using the equipment, we can do more data collection and also more interesting or some other interesting, you know, research directions that we can test or we can demonstrate. Is that a new this technology really can work for, you know, permafrost degradation study? We never thought of that before. But you know, once we got experience in State College, we built up confidence. We see, oh, it is really possible, you know, can record some, you know, very small signals because again, because the technology is really on the laser, you know, nanometers, even if you have a very small, you know, environmental change because the sensitivity of the laser that it can still detect these small changes. For example, permafrost degradation, you just cannot see that...

For long term, you can see that. But for the short term you didn't see the degradation. Where is the degradation? But because our, you know, equipment, we actually can see that from our data results.

Host

That is, I mean... that is amazing. This technology has so many connections and abilities to learn about our world, from moving people to moving water to moving land.

Tieyuan Zhu

Yeah, this is exactly, you know, why I'm really interested in how the Earth's surface or critical zone is being modified by something. Because in the short term, this modification is really hard to capture by our traditional sensors. You can imagine, you collect the data today, and then you don't collect the data tomorrow or the day after.

But if you collect the next year and then we'll compare this data, you actually don't understand what physically happened between today with data because there are a lot of things going on. But if you have this technology, this technology can collect the real-time data. This real-time data really can give you the clue about what happened between today and then the day in next year because they really capture everything they have. And then you can, using this data, really improve our understanding of all this physical cause of this change. So that's the amazing of this technology.

Host

Thank you so much for being on here. I really enjoyed talking with you.

Tieyuan Zhu

Thank you, Kevin. Yeah. If you want to reach out to me, please email me at tuz47@psu.edu.

Host

This has been season five, episode five of Growing Impact. Thanks again to Tieyuan Zhu for speaking with me about his project. To watch a video version of this episode and to learn more about the research team, visit iee.psu.edu/podcast. Once you're there, you'll find previous episodes, transcripts, related graphics, and so much more.

Our creative director is Chris Komlenic, with graphic design and video production by Brenna Buck, marketing and social media by Tori Indivero, and web support by John Stabinger.

Join us again next month as we continue our exploration of Penn State research and its growing impact. Thanks for listening.

Some images on this page are from Zhu, T., Shen, J., & Martin, E. R. (2021). Sensing Earth and environment dynamics by telecommunication fiber-optic sensors: an urban experiment in Pennsylvania, USA. Solid Earth, 12(1), 219–235, and are used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. You can access the original publication at https://doi.org/10.5194/se-12-219-2021.