35-minute listen/watch | 20-minute read | 1-minute teaser

Solar energy's surge, driven by cost efficiency and climate change urgency, is prompting a rapid transition to a renewable energy source with substantial land requirements. This trend parallels past land rushes, like the contentious Marcellus Shale gas movement, triggering reservations among farmers as well as rural citizens and landowners. To inform just and sustainable rural land use with solar, a research team is working in rural communities to determine the potential for harmonious coexistence between solar and agriculture.

Transcript

Intro

On the sustainability side of solar farm development, it's really important for us to think about managing this land in a way such that the quality and state of the land is as good or better than when the solar farm was first built. So, when that lease is done, we can return it to a use like agriculture again, we're not causing net harm to the ecosystem or the land as part of the development process.

Host

Welcome to Growing Impact, a podcast by the Institute of Energy and the Environment at Penn State. Each month, Growing Impact explores the projects of Penn State researchers who are solving some of the world's most challenging energy and environmental issues. Each project has been funded through a seed grant program that's facilitated through IEE. I'm your host, Kevin Sliman. Solar energy stands out as a sustainable power source capable of meeting our energy needs without contributing to climate change.

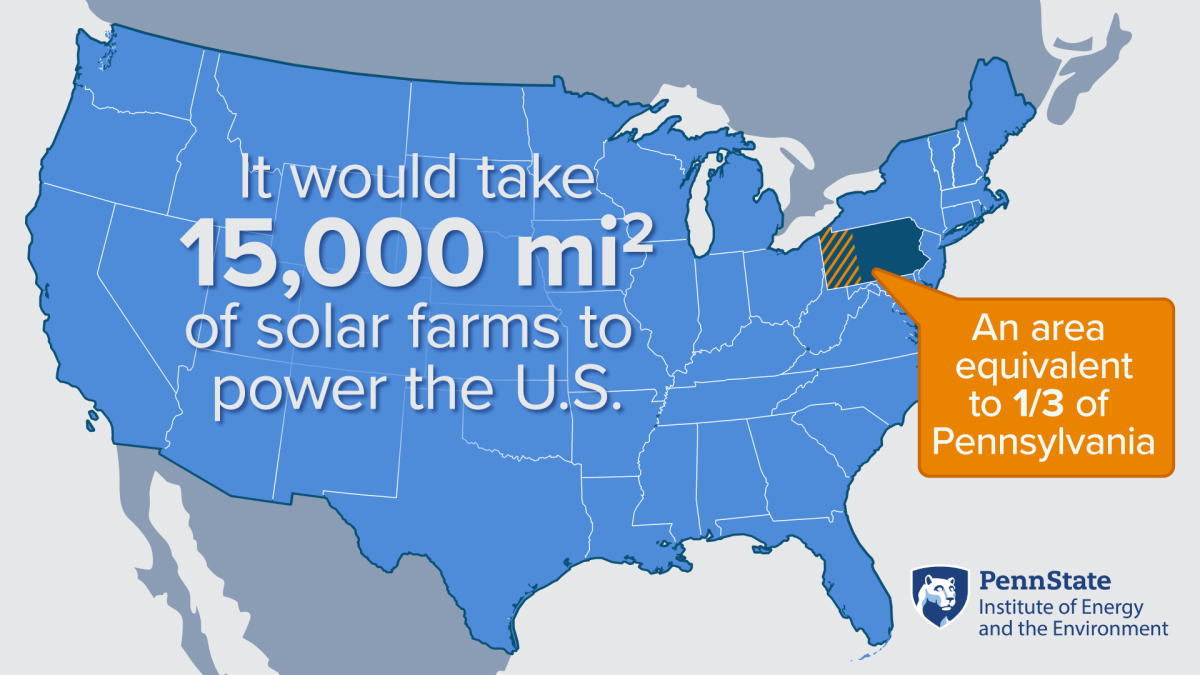

Despite its climate benefits, the transition to solar power is not without challenges. One of which being the substantial amount of land needed. The estimates vary, but it would take approximately 15,000 square miles of solar farms to power the entire nation, a landmass equivalent to one third of Pennsylvania. The urgency to accelerate this transition due to climate change raises critical questions, such as: Where can these solar panels be strategically placed? How will the ecosystem be impacted? And who will be affected by this transition? Addressing these questions, a research team is exploring the equitable and sustainable integration of solar farms into existing farmland in Pennsylvania.

I'm very thankful that you are able to join today. Thank you to each of you. To start with, can I have the team go through and introduce themselves?

Stephanie Buechler

Hi, this is Stephanie Buechler and I'm an associate research professor in Ag Sciences Global, and I also have an Extension appointment at Penn State. And my background is in issues around gender, the environment, and especially environmental change and as it affects water and energy resources.

Kaitlyn Spangler

Hi, it's Kaitlyn Spangler. I'm an assistant professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education in the College of Ag Sciences here at Penn State. And my work is largely interested in understanding how agricultural landscapes can become more biodiverse and what that biodiversity means for communities that use, manage, and are implicated in these landscapes and the transitions of those landscapes.

Lauren McPhillips

Hello, I'm Lauren McPhillips. I am an assistant professor co-appointed in civil and environmental engineering, and agricultural and biological engineering, and I work across areas that include water and soils management. I have a lot of interest in nature-based solutions, and I like to think a lot about how we manage human impacts on the landscape and how we can do better in the future in minimizing the impact of ways that we develop the landscape.

Host

Solar energy is on the rise. Can we explore why solar energy is becoming more popular and showing up in more places?

Stephanie Buechler

One of the things is that the cost of solar has gone down dramatically, and one of the reasons for that is ramped up production in many different countries and then making it cheaper in the US marketplace for purchasing solar panels. There's also been concurrently at the utility scale, you know, the development of solar farms. You have both private actors as well as public utilities and the private sector working together to really expand the use of solar energy at a time when dependence on foreign oil has become more and more problematic due to geopolitical issues.

Lauren McPhillips

I'll just step back a second and say that we're experiencing climate change, and we need to find energy sources that are renewable. And so, we have political goals that are pushing us towards that. We also have reduced cost of certain types of renewable energy, including solar. And so it's becoming something that private organizations, that governments are looking towards in order to try to meet these renewable energy goals.

Kaitlyn Spangler

And with that we've seen in recent years, especially a growth of state and federal policies that have incentivized diversification of our energy portfolios across these multiple scales. So, you know, recently in the Biden administration we've seen the Inflation Reduction Act, which has a whole host of incentives for folks across private and public sectors to develop solar, as well as residential communities to adopt solar. So we've seen an influx of policy that's starting to support these more than we've seen in prior decades.

Host

So with solar energy, these installations obviously they take land. So can we discuss land use and contextualize it when it comes to solar?

Kaitlyn Spangler

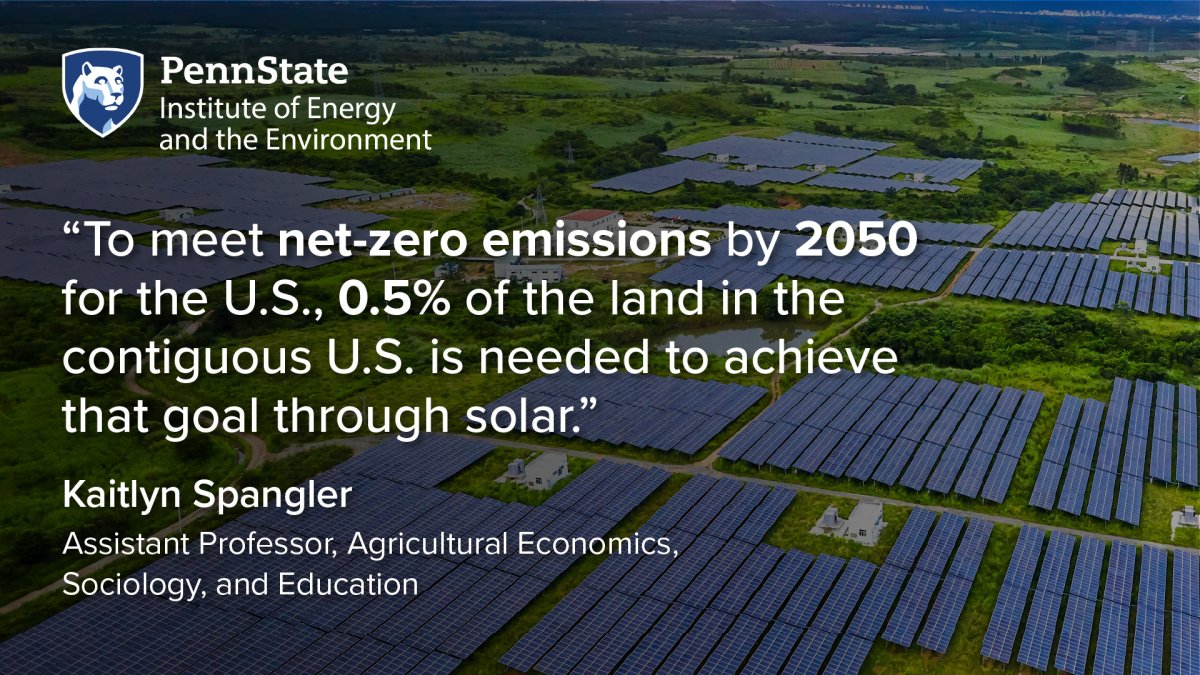

So it is land-intensive in a relative sense. So, it is one of the kind of main concerns and at least challenges or questions that we want to tackle in how we expand solar well and sustainably. So, you know, one of the statistics we might come across is that to meet net zero emissions by 2050 for the US, 0.5% of the land in the contiguous US is needed to sort of achieve that goal through solar.

So that can kind of be seen as a large amount of land and a small amount of land depending on where it is and who's kind of bearing the costs and bearing and receiving the benefits of that kind of development. And there's this large question of where that land is and how it's kind of intertwined in the rest of our energy portfolio.

Stephanie Buechler

One of the things that, you know, urban rooftop solar teaches us is that it doesn't need to be on land that then is not used for anything else. So if you have rooftop solar, you're not actually using more land, you're putting it on a roof. But also in rural areas then you can have dual use of land for if you have agrivoltaics, you can use that land below the panels to produce food. And so this is one of the things that our research is examining because there is less known about how that is possible in the Northeast US.

Lauren McPhillips

So you could say that we're trying to minimize the conflict that can occur when thinking about where to put solar and other ways we might use that land. So what Stephanie was mentioning about urban areas, we're talking about like rooftops or also parking lots where solar could be added as a shade structure. And this is great because those are already hard surfaces where there's not really concern with any sort of impacts on the land because it's just a hard surface there and you're actually getting added benefit on top of the existing use.

But there are issues there with policies, with cost on some of these things, with the structural challenges of retrofitting, which is why we're also seeing this massive use of arable land. And so this leads to questions about, you know, the type of land that's then being used in these open spaces. And it turns out that flat, well-draining lands that are really great for agriculture is one of the most ideal types of land for solar farms.

And so that's where you hit this conflict, and so it's important to think about are there ways to overlap uses with solar and some form of agriculture, or can we also think about marginal lands, lands that maybe can't be used for agriculture? And so we remove that conflict—lands that might be steep, lands that might be formerly mined, things like that.

Host

The title of your project is Sustainable and Just Pathways to Agrivoltaics in Pennsylvania. First, can you define agrivoltaics? And second, can you explain what you mean by sustainable and just?

Kaitlyn Spangler

Yeah, so agrivoltaics, as we mentioned briefly, is the intentional dual use or multi use of including solar as solar photovoltaics or solar panels on land that is also at the same time used for other agricultural purposes. And we're going... we're using a very broad sense of the term agricultural here because it can include, as Stephanie mentioned, active food production. Food meaning specialty crops like vegetables and fruit.

It can also mean, in some cases, a maybe more commodity production. So corn and other types of more, of crops we see on larger farms. It can also include animal agriculture, grazing of small ruminants like sheep or even large ruminants like cows or other cattle. And there's also an inclusion in agrivoltaics of constructing pollinator habitats, native plant habitats that can promote pollinator-friendly production. So there is I think the term, the definition of "agrivoltaics" is excitingly shifting and a bit dynamic because it is a very nascent form of land use.

Host

"Sustainable and just"—when you are thinking about that with your project, what does that mean for this work?

Stephanie Buechler

So I look at it from the very, you know, micro level of the household to make sure that if it, if those panels are put on the land, who is benefiting within the household? What is it going to be used for and what is that use supplanting? So in the sense of like what did that land used to be used for? Who within the household used to gain a benefit from that use of the land and who will benefit from the use of that land under agrivoltaics? That's very important, because what we don't want is to create a situation where vulnerable actors become even more vulnerable.

Kaitlyn Spangler

So there are these sort of three realms that we can think about what an energy transition might look like in a just-oriented context. And this is, as Stephanie was mentioning, both in the sort of outcomes of what happens when we're producing energy, who's benefiting and who might not be. But it also is kind of all throughout the entire process of this transition.

So all from the legal negotiations, these procedural justice processes of how is this transition being negotiated and who's part of that negotiation and who's not. As well as whose rights and interests are being represented—that's this recognition piece of justice. So how, what are the power dynamics that are affecting who is being recognized and represented and who is not?

And then also this distributive. So that's more of these outcome-based products of how are the... how are things being distributed either like quite literally through the energy grid, but also in these benefits and drawbacks. A big piece of talking about solar is that these are relatively long-term transitions of land transitions that oftentimes, not to get too technical in the weeds, but a lease for putting solar panels in is at minimum 25 to 30 years.

So this relationship between whoever is kind of part of this land transition is a long term one. And there are a lot of implications to think about temporally and spatially of who's benefiting and who is not, who's represented and who's not, and how that might change over time.

Lauren McPhillips

On the sustainability side of solar farm development, it's really important for us to think about managing this land in a way such that the quality and state of the land is as good or better than when the solar farm was first built. So when that lease is done, we can return it to a use like agriculture again, we're not causing net harm to the ecosystem or the land as part of the development process.

Host

Can we talk about the goals of the project?

Kaitlyn Spangler

So the first piece is with Dr. Trevor Birkenholtz and a grad student that works with him, Harman Singh, that is using a language-processing model to first kind of see what we can, what stories we can tell about how news media have talked about solar development in recent decades or sorry recent years, not recent decades, and how that might compare and/or differ from the stories that we can tell or have told about hydraulic fracturing and Marcellus Shale development in Pennsylvania specifically.

So we're sort of using data that we have accessible to us and models we have accessible to us to see how we might contextualize a bit of a deeper historical context in terms of energy development in Pennsylvania—specifically through a media lens. Another piece is to what Stephanie and I and another student or a former student Karen Olmedo is working on is first distributing a survey to producers, farmers, active farm workers, folks who are operating farmland in Pennsylvania, and trying to locate folks who are already doing some form of agrivoltaics who are interested in doing agrivoltaics or are in some way entering into this agrivoltaics space.

Because it is so nascent, it's hard to find those people and know what they're doing. And so there is a gap in kind of getting a sense of what folks are doing across Pennsylvania and how ongoing research efforts might help what they're already doing or hoping to do. And another piece, and I'm sure Lauren can build on this, is kind of enhancing and supporting, you know, already the existing work of soil health testing and understanding what's actually happening on the land beneath solar panels at sites where we're already, we've already been doing some form of agrivoltaics in Pennsylvania.

Lauren McPhillips

So you can see that there's a lot of feedbacks going on, as you really alluded to Kevin, between the social and the environmental realm here. And so like we're trying to understand these perceptions, which are likely in some ways relating to people's thoughts about the aesthetics of these systems, but also how they might affect the land, how they might affect their economy.

And so we're trying to understand how some of these things tie together. And so if we can document that developing solar farms in a certain way is actually having net benefits to the ecosystem, to the functions that are provided, then perhaps that can feed back to changing perceptions and changing local policies that support development of solar farms.

Stephanie Buechler

Yeah, and then we hope to have some research products, if you will, outputs that really start to inform decision-making around agrivoltaics, specifically for Pennsylvania. And we hope as well that this study can inform what's going on in other states in the US, but also internationally. One of the outputs might be research briefs and policy briefs. And those, I think, can reach a large audience and can hopefully then lead us to be able to make those connections between other places and maybe best practices in other places and also lessons from here that could be applied elsewhere.

Host

What ways can agriculture and solar energy complement each other? And conversely, can we discuss some of the challenges and/or barriers to solar adoption?

Lauren McPhillips

So there are definitely some direct positive feedbacks there. A couple examples are that one form of agrivoltaics could be grazing. So on a solar farm you don't want the vegetation to get too tall or it could shade the panels and it could decrease the production of solar energy. And so one means of managing that is to have mowers out there, which is then probably burning more gas and kind of negating some of that carbon footprint reduction that we're trying to get from solar. But if we have sheep out there that are eating down that grass, those sheep can be moved between different sites and used to be sheared for wool or whatever other uses, but basically be supporting a grazing farming industry and also cutting down that vegetation at the same time without using mowing.

Another one is by having healthy vegetation around the panels in certain climates, especially those that are warmer than ours, you can actually get some cooling just from the transpiration of water—when plants are cycling water, it can sometimes actually help provide some cooling to the panels, especially in places like Arizona. They've observed some impacts like that.

Kaitlyn Spangler

Yeah. Building off of that, too, there's a pretty well-known agrivoltaic research farm in Colorado called Jack's Solar Garden, and I think it's about four acres, it’s relatively small. But one of the things they're finding there, Colorado is also drier and warmer than Pennsylvania, but that the shade provided by the panels, should we plant directly underneath the panels or even between them, helps certain crops grow that like shade or at least some shade.

I guess related to the challenges and barriers, related to what we know, and we don't know about agrivoltaics is that a model of expanding solar, like we've mentioned, is at this utility scale, having enough of that land that could generate enough energy to contribute to like, to be sold back to the energy grid. So it's at this utility scale. And right now, there is a more standard model of expanding that kind of solar that is not necessarily it's not, it doesn't necessarily have agrivoltaics in mind. So there is more of a push to get those panels in the ground more quickly. And the long-term planning of what's going to happen underneath the panels is not necessarily being planned for before those panels go in. And this is something that I've observed in interviews with producers and solar stakeholders prior to this seed grant and informing this seed grant that we have a maybe more standard model of mowing the grass, like Lauren mentioned, without necessarily thinking how sheep might be able to fit underneath there or if there is really any sort of incentive or agreement to at some point put sheep there. So there is maybe a gap and a barrier to the long-term planning of agrivoltaics at larger scales in solar adoption or solar expansion.

Stephanie Buechler

We don't really know how it will change rural livelihoods to have agrivoltaics being practiced or, you know, and we don't even know what it will really do to livelihoods yet to have, you know, large scale solar projects on farmers’ lands that are tied to the grid without agrivoltaics. So we need to sort of really see what can agrivoltaics bring into rural livelihoods. We need to sort of study what is already going on. But we also need to, you know, provide a sense of what might happen in the future under different scenarios.

Kaitlyn Spangler

A main concern for farmers and for rural communities is loss of farmland, loss of active farmland. And that is that's a difficult conversation because we know that we don't need a large percentage of land, land including farmland, but also other types of marginal land or other type of land that we've kind of touched on here. We don't need a ton of land, percentage wise, for us to meet our solar goals, but the loss of any farmland is controversial and difficult, both in cultural and aesthetic values in that farmland, economic value of that farmland, and ecological value of the farmland.

So that's one piece of it. And I think it's important to kind of add in a little bit of a nuance here that currently, as it stands, preserved farmland—so farmland that is protected under the farmland preservation program cannot host solar panels. It is like a prohibited use on preserve farmland. One of the questions around agrivoltaics that we've been sort of talking with the Pennsylvania Farmland Preservation Association about how they're navigating this is if agrivoltaics can be considered a preservable type of farmland use.

So in this, again, this kind of shifting definition of what counts as agriculture in agrivoltaics may complicate the ways that we can preserve a farm that has solar panels and has some form of active agricultural production, because we don't quite know what that looks like 30 years, let alone 100 years into the future. So from a preservation standpoint, it's a challenge to think about how we can ensure that this land can be farmed and remain so to be able to protect it in these programs that we have. So that's just another piece I think, that is worth mentioning in this loss of farmland, preserving farmland conversation.

Lauren McPhillips

And one of the barriers that's emerging is differences in municipal ordinances and zoning and where solar farms are allowed. And this again, ties back to this perceptions aspect and how this transition is happening and concern that it might be having net negative impacts in some way or another. And so one of our colleagues at Penn State has been looking at kind of the huge variation in ordinances out there. Mohammad Badissy has been doing some of this work. And increasingly some communities are changing their ordinances to prohibit solar farms, and this is a concern because we need to reach renewable energy goals to, you know, to be combating climate change. But as has been highlighted here, you know, we don't want to be doing it in a way that is causing net harm to people or ecosystems.

So I think we're trying to fit in there and to this how... how can we do better? And ensure that this is happening in the right way so that we can alleviate some of those concerns and facilitate this big transition that needs to happen.

Stephanie Buechler

And we should reiterate that this is not the first time that energy projects have been sited in rural areas. So, you know, fracking being one of them. So, you know, we have to look at rural sites as kind of continued sites of energy production and also the sites of extraction of minerals. And so of those different kinds of industries, we have to contextualize solar, right? And we have to think about it in environmental terms as well, comparing the impact of solar versus the impact of, you know, maybe coal mining to fracking, to... And we have to think about that in in the sense of our overall goals of, you know, environmental concerns for the planet.

Host

For the parts of America that may not be familiar with fracking, because those people living in those areas where fracking was occurring and impacting their communities, it was ,is fairly familiar. But there were parts of the of America right that were fracking wasn't happening as much or maybe the news didn't travel to as much. So please—how does investigating this transition mirror that idea that fracking transition in communities in recent past?

Kaitlyn Spangler

Pennsylvania is a site of hydraulic fracturing through the Marcellus Shale development. And this was largely happening, let's say around 2008 to 2011 were maybe like the peak years of when this was occurring. But we're still seeing the legacies of that type of energy development in complicated ways across the state. And a lot of what this, how this relates to solar is largely in these procedural elements of "landmen" is the sort of colloquial term, or folks that work for developer companies that are approaching landowners. In the case of fracking, that doesn't necessarily mean farmers. It's also, you know, just landowners in general, approaching landowners individually or privately and offering a lease contract, compensation for access to their land to develop in this case, to sort of frack the Marcellus Shale gas, to extract gas, natural gas out of the Marcellus Shale. And you're seeing a parallel with that in solar.

We have these landmen, land people, but the term is landmen, are folks that are representing solar developer companies that are approaching farmers individually and offering lease contracts, use their land for solar development. And of course, there is a divergent outcome here. There's an important distinction between types of energy—renewable, nonrenewable—and the ecological implications of those.

But in the process of it, we want to be careful about not necessarily replicating history in unhelpful ways and that is a piece of this research, is understanding what these lease negotiations will look like for solar leasing and how the representation and rights of the farmers and landowners are being offered the contracts is different from maybe some of the, from some of the negative consequences we saw of hydraulic fracturing.

You know, there's a long legacy of that type of injustice of the effects of what it meant to have a well pad on your land and whether or not that was clear at the time of signing. One of the ways that landowners in Marcellus Shale development were able to come together through that peak of that development is through organizing, contacting each other, connecting with each other, understanding how their leases differed from other neighbors and community members across the state or across the region.

So there was these coalitions of landowners that really helped them advocate for fairer lease contracts and that's something that at present is not, we're not quite seeing the ability to organize and talk to each other in solar development. Again, there are important distinctions, but we're seeing a sort of isolation of farmers and landowners across the state engaging in solar lease contracts and not necessarily having access to talking to other farmers and landowners about what it looked like or looks like for them and how they might advocate for something better together. So I think that's an important piece of it, and it's a very complicated one that I want to make sure is part of the conversation.

Host

What will success look like as this, whether you want to call it the seed grant project draws to an end and maybe you can think about it from that standpoint and what maybe next steps are, but also maybe as a larger project, maybe what success looks like at the end?

Lauren McPhillips

I think success can be measured in many ways, right? So we're hoping to get to some specific deliverable, synthesizing some of the understanding we've come to so far. But part of the success, too, is just building collaborations and building networks beyond Penn State amongst our communities and governments to continue and expand this work, because this little seed grant isn't meant to solve this whole problem in one year, but just start to seed the effort to be able to help facilitate this sustainable and just transition.

Stephanie Buechler

We hope to bring some of the voices of the people that we talk to to a larger audience, and that's one of my main goals as a researcher, is always to do that because I can be that bridge. I hope that my work can also not only inform, but really act to, you know, be an exchange platform between different groups from different parts of the country, and the world, and so in that we would need a larger project. And I think this acts as a way to start that whole exciting process.

Kaitlyn Spangler

We are by no means the only group of folks studying or working on or with solar and solar development at Penn State. There's a huge network of energy and solar folks, and so any resources to coalesce those efforts is just great. And so that's, that is a success in and of itself. And especially if it and the extent that it continues.

And also I think just a main success is a broader and deeper understanding of the sort of state of agrivoltaics across Pennsylvania, because it is so nascent and because it is geographically hard to find. And so the ability to locate and understand more deeply what's happening already and what might be possible is hopefully a solid foundation for continued work.

Host

Thank you very much. Stephanie Buechler, Lauren McPhillips, Kaitlyn Spangler, I really appreciate your time.

Kaitlyn Spangler

Thanks. This was fun.

Stephanie Buechler

Yeah, it was great.

Host

This has been season four, episode six of Growing Impact. Thanks again to Stephanie Buechler, Lauren McPhillips, and Kaitlyn Spangler for speaking with me about the research. To watch a video version of this episode and to learn more about the research team, visit iee.psu.edu/podcast. Once you're there, you'll find previous episodes, transcripts, related graphics, and so much more.

Our creative director is Chris Komlenic, with graphic design and video production by Brenna Buck, and promotional and social media support by Tori Indivero. Join us again next month as we continue our exploration of Penn State research and its growing impact. Thanks for listening.