This blog entry was written by Clare Randolph, Dylan Davis, Chiamaka Anyanwu, Karen Pham, Dani Buffa, Ebony Creswell, Abiola Ibirogba, and Kristina Douglass on behalf of the Olo Be Taloha (OBT) Lab.

Traditional ecological knowledge held by Indigenous groups around the world is key to understanding resilience and cultural survival in the face of intensifying climate change. Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) refers to an evolving, intergenerational compendium of information acquired by local, Indigenous and descendant (LID) communities through interactions with the environment over hundreds to thousands of years. It is based on rigorous observations of the local environment built upon generation after generation. While non-Indigenous researchers are starting to understand the importance of TEK for future sustainability and mitigating impacts of climate change, it has historically been underrepresented (and undervalued) in Western scientific literature. TEK is an important component of climate research going forward, but the disproportionate impact of climate change on rural communities is threatening the transmission of TEK to subsequent generations.

There are many examples around the world of the importance of TEK in addressing climate and other ecological disasters. In the western United States, Indigenous communities have long utilized prescribed burning for managing ecosystem health and stability. Government suppression of natural and prescribed Indigenous burning has resulted in rampant wildfires costing over $10 billion in damage to infrastructure in 2020 alone. Only recently have fire officials started to acknowledge the importance of such TEK for managing fire regimes by collaborating with Indigenous groups to amend California fire policies.

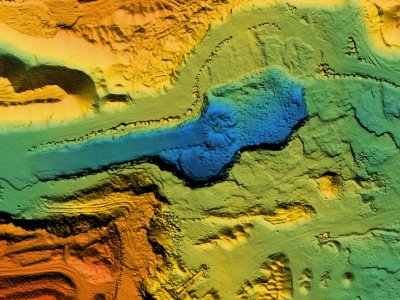

A Penn State research group led by Kristina Douglass, the Olo Be Taloha (OBT) Lab, investigates human-environmental interactions in island and coastal regions, and is revealing that the loss of TEK and linked practices increases community vulnerability to climatic and environmental change. Since 2011, the Morombe Archaeological Project (MAP), the Madagascar research partner of the OBT Lab, has been conducting archaeological research projects in and around the Velondriake Marine Protected Area in southwestern Madagascar. MAP is a collaborative, community-based team that studies human-environmental dynamics on Madagascar and how this history is reflected in Malagasy communities today. In addition to documenting TEK, MAP and the OBT lab are committed to developing new approaches to knowledge co-production, some of which have been featured in Nature.

Recently, the MAP team, in collaboration with researchers at Penn State’s OBT Lab, have been engaged in the Vezo Ecological Knowledge Exchange (VEKE). To launch the VEKE project, a delegation of Vezo community members and US-based researchers, traveled together to the Smithsonian and visited research facilities at Penn State. This visit promoted knowledge exchange between local communities and researchers in the process of recording TEK associated with

Malagasy biological specimens at the National Museum of Natural History, and cultural objects at the National Museum of the American Indian.

An article, written by the MAP team came out in 2019 outlining some of the knowledge co-production practices that were foundational to creating the VEKE. The OBT lab and the MAP continue to follow the framework outlined in this paper as the VEKE project continues. Since 2020, the VEKE continued with a series of virtual workshops where Vezo delegates participate in discussions about the value of ethnobiological data and intergenerational ecological knowledge. The ideas generated by the VEKE project inform all OBT Lab/MAP projects moving forward.

Building knowledge co-production in Madagascar is critical since many communities in the country are experiencing increasing threats to their livelihoods and landscapes. However, similar threats are felt by communities around the world. This includes many on the frontlines of the climate crisis that have hundreds to thousands of years of intergenerational knowledge and experience in coping with climatic fluctuations. To best understand and combat the ongoing climate crisis, researchers engaged with questions that have direct impacts on vulnerable communities must prioritize the recording of TEK and engage in knowledge co-production. Conserving Indigenous knowledge systems will ensure success for future policies and initiatives that address the unprecedented climatic variability around the world.

Historically, the typical Western scientific approaches have downplayed TEK, claiming that it is not “objective.” However, TEK is rooted in empirical observation, just like Western scientific approaches. In fact, the continuous time series of data points contained in TEK is invaluable for contextualizing information gathered by researchers at their field sites. In the same way that TEK itself has been undervalued, the trust, relationships, and skills needed to work with TEK have also been assumed to be non-essential to the production of science.

If researchers wish to understand and address the impacts of climate change as well as rising inequality, Western science must recognize the value of and integrate TEK and the knowledge held by place-based Indigenous communities. All scientists and researchers looking at issues relating to the climate crisis need to critically reflect on the degree to which they work collaboratively with and for LID communities.