23-minute listen | 14-minute read

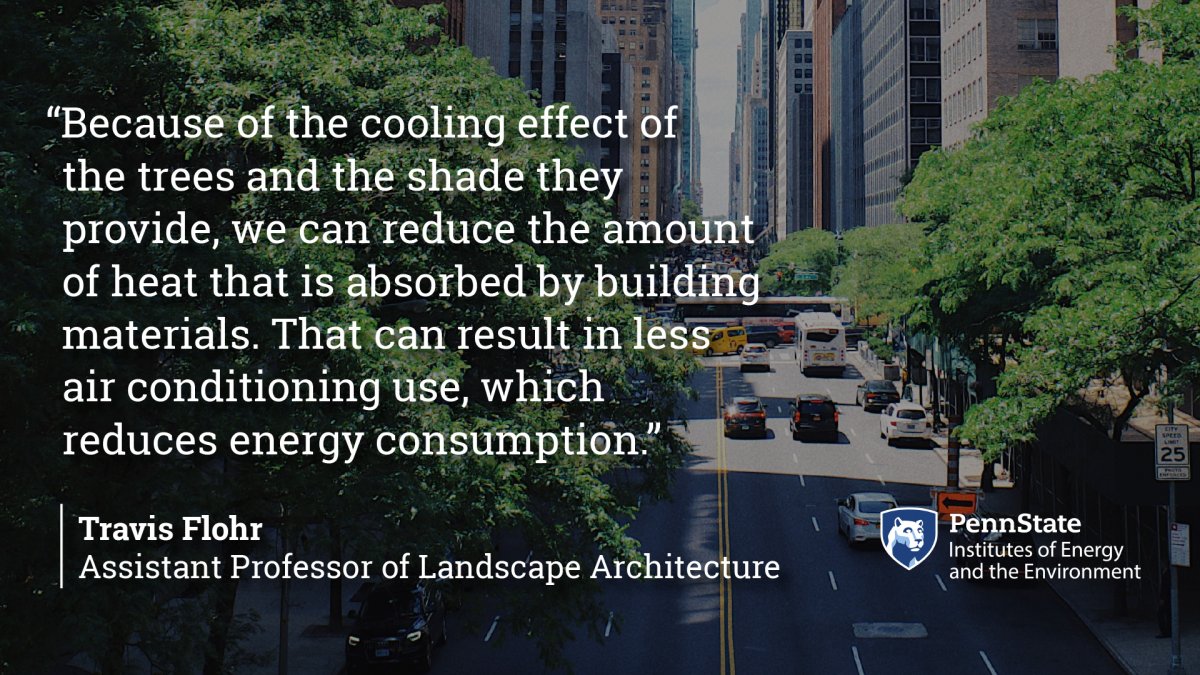

As cities are built, a lot of vegetation is replaced with building materials such as concrete and brick. These materials absorb the sun's heat and then radiate it back into the atmosphere. This leads to urban heat islands where cities are much hotter than the surrounding areas. But trees offer shade and cooling, reducing the temperature in cities. So, what is stopping cities from planting more trees? That is what one research team is investigating.

Transcript

INTRO: So yeah, we've taken out forested area or meadows or prairies that often are cooler than urban areas because then we replace it with asphalt, which absorbs and retains a lot of heat from the sun and then releases it back out over time.

HOST: Welcome to Growing Impact, a podcast by the Institutes of Energy and the Environment at Penn State. Growing Impact explores cutting-edge projects of researchers and scientists who are solving some of the world s most challenging energy and environmental issues. Each project has been funded through an impactful seed grant program that's facilitated through IEE. I'm your host, Kevin Sliman.

HOST: Trees in cities have multiple positive effects, from shade and cooling to higher property values and improved mental health. But the situation is far more challenging than simply saying, plant more trees. On this episode of Growing Impact, I speak with Travis Flohr, who, along with his team, is investigating the barriers cities could encounter when designing and planning urban forests. The team is also exploring if these plans for urban forests are enough to impact the urban heat island as climate change continues to intensify.

HOST: Welcome, Travis to Growing Impact.

Travis Flohr (TF): Hello to everyone. I'm Travis Flohr, and I'm an assistant professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture here at Penn State. I'm a bit of a designer, but I'm also, I have a planning background and so I deal with some policy as well. But my research tackles how to help communities and households adapt or manage, also mitigate impacts of extreme weather events and the degradation of ecosystems. Mostly to ensure that they still get those benefits and services that they've had the privilege of having and the past into the future, such as clean air, water. But really, in particular, where I focus is urban microclimates and urban heat island effect. Regrettably, my team couldn't be here, so I want to ensure that I recognize their contributions. And so I'd like to thank Lilliard Richardson, Margaret Hoffman, Hong Wu, Justine Lindemann, Mehdi Heris, and Laura Garcia.

HOST: Let's talk about these urban forests. Can you describe an urban forest and talk to us a little bit about why they're in decline?

TF: There's a lot of different ways in which we can define an urban forest, and they come in all different shapes and sizes. So similar to non-urban forests, it could be patches of actual forested land that are within an urban environment. So at its most straightforward, it's that. But more broadly, when you talk about urban forests, you also talk about the whole network of systems of different kinds of trees and ways in which trees are represented in cities. So it could be forested or woodlands. It could be just groups of trees in parks. It could also be individual trees located in urban areas that could be parking lots, street trees.

HOST: For the decline component. So maybe I should just ask the question, are they in decline?

TF: Generally? Yeah. Yeah. Every city is different, of course, but generally speaking, they are in decline. And a lot of previous researchers have documented this. And they've really dug into the details of why. Some of it is just land development. You have urban or vacant land that has an urban woodlot on it and you clear it out to put in more commercial or housing. So some of it is just the change of the urban environment and development that happens. But also increasingly its disease and pest. So things like the Dutch elm disease has wiped out large swaths of elm trees, which were fantastic urban trees. So of course, cities planted a lot of them. And sadly, there have been and are being decimated. We have things like the emerald ash borer. So a lot of our go-to urban trees, that are aesthetically beautiful, long-lived, big shade, big amounts of shade. There, just disease and pests. Also, urban environments are tough for things to grow in. They often aren't given the soil volume they need to thrive. And so they struggled from day one. They're just often not as long-lived as trees typically would be in a sort of more open, rural, large soil-volume environment. It's really that impervious surface because they need to well, impervious surface pipes, utilities, buildings, foundations. But yeah, they really need the water infiltrating into roots and impervious surfaces prevent that. It's also the air and gas exchange that soils have in order for healthy soil activity and microorganisms and things that sort of have that symbiotic relationship with the trees to help them thrive. And a lot of the urban pavement and environment just covers that all up.

HOST: So you had or have, I should say, in IEE seed grant project called Connecting Policies to Actions for Creating Just, Biodiverse, and Climate-Resilient Urban Forests. Could you provide just a little bit of a brief abstract and a little bit of the goal of the project?

TF: Sure. A lot of cities and communities and we're working in Pittsburgh, have amazing tree plans. And so I have to give credit to Tree Pittsburgh. They're doing a fantastic job with sort of setting benchmarks and trying to maintain and increase their urban tree canopy. And they're doing a fantastic job. I know some people at Penn State and Penn State Extension such as Bill Elmendorf, are involved and a whole host of other groups as well. And they really have an amazing plan. But our question is I'm on the design and planning because again, I'm a landscape architect by training what are the barriers and implementing that plan that they have? Because we're still not sure, are they hitting their targets and benchmarks. And then there's this other sort of a couple of outstanding questions that we hope to tackle, is it enough? Under climate change and in my area, in particular urban heat island, are these benchmarks enough? And if there are disruptions in trying to achieve that benchmark, what does it do for those benefits that we get from the urban forest? Can it be maintained? Is it radically decreased? And what can we do about that? And then often I find having been in professional practice as a designer we're not sure how the design process works in this regard. Are designers reading and interfacing with this plan? How is that affecting their design decisions on private development and private properties? Are they looking at these benchmarks and biodiversity targets and adjusting their designs accordingly? So we really want to dive in to find out how's this plan being implemented on the ground and what are the friction points and how might we resolve them to ensure we have those benefits in the future.

HOST: Could you define urban heat island for us?

TF: The urban heat island is the result of the way in which we develop our urban environments. That through the combination of things like concrete, asphalt, brick, the types of building materials we use, and the replacement or removal of vegetation often tree vegetation in our locale or our state. So yeah, we've, we've taken out forested area or meadows or prairies that often are cooler than urban areas because then we replace it with asphalt which absorbs and retains a lot of heat from the sun, and then releases it back out over time. So generally speaking, urban heat island is the cities are hotter, they're way hotter than their surrounding environment. And it ranges depending on your climate and location, but it can be pretty significant. It's definitely hotter in a different way because it'll disrupt airflow. It disrupts weather patterns. And in some cases, they can be a degree, two degrees up to 7 degrees Fahrenheit higher during the day. Some places even more so. But then also at night like when you're trying to sleep and if you don't have air conditioning, it can be two to five degrees hotter through the night as well. And so you also don't get that sort of daily heating and cooling because the urban environment disrupts that.

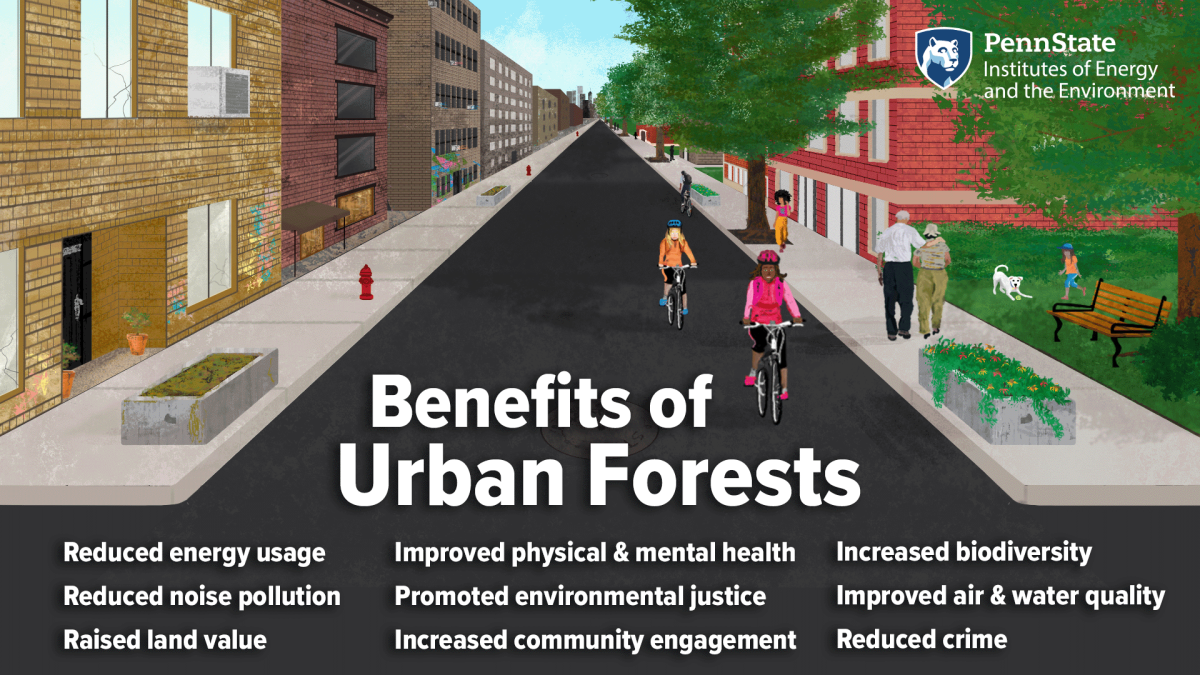

HOST: Could you talk about the benefits of urban forests, including in terms of climate change and biodiversity?

TF: So a lot of the benefits are increasingly, maybe not everyone understands it, but they're becoming pretty widely understood and accepted. Air quality, so they improve urban air quality. They improve urban water pollution and help sort of control stormwater runoff and a variety of ways. They can alter heating and cooling costs even at a building level. So if they can reduce the microclimate or the urban heat island effect, then we're cooling our environment less indoors. They can increase social benefits and economic benefits like they do increase real estate values. They've been linked to improved physical and mental health. They've even in some places been associated with reduced crime rates. So there's a lot of benefits or ecosystem services there. They can and been shown to increase community and neighborhood pride and active living, helping people get outside, especially when it's warmer because of the cooling effect of the trees. So where the benefits of climate change come in is the more we can reduce the need to heat and cool, it's less energy consumption. So that's a more direct sort of benefit. And then if we get enough of them, they can also sequester carbon and other things. And so definitely help climate change in that regard. The way in which bio diversity comes in is back to why are they declining? And so we don't have those benefits obviously, or as much of them, or they're not being maximized because the forest isn't thriving. Often when diversity decreases because of things like pests, there are whole neighborhoods that have lost their tree cover. And so now those neighborhoods do not have those benefits, unfortunately, without restoring their tree canopy. And if you don't have diversity of ages in there and you lose a bunch of old trees, it takes a long time to re-grow them and get their full benefits.

HOST: Do you see a connection between urban forests and equity?

TF: Oh, absolutely. This is something that it's one of those things that I intuitively knew. But until you really dig into it, you don't really understand the depth of how and why. And so sadly, I'll start there. If you mapped urban trees and there's some groups, I think, yeah, Dexter, there's a gentleman I believe named Dexter Locke and a lot of his associates, they did a residential housing segregation, urban tree canopy across 37 US cities. And there's a whole bunch of others that have done similar work as well. But their maps, when they map these urban tree covers, almost lined up exactly with income and race. And I say sadly because it's the decades of the discriminatory policies like red lining and the banking industry giving loans and investment in communities of color and also in low-income communities, that the sparsest least amount of tree, urban trees are in these neighborhoods. And it's just, it's a systemic thing that has just continued. And now we're sort of reckoning with yeah, it's a challenge because now I know there's some research in Detroit where they got the city non-profit. They had some federal funding. They got some foundational funding, and they were beginning to come into a lot of these communities and started to replant trees. But it really caused concern from the residents because you've been disinvesting in us for so long. What are we, what's happening now? They had a lot of questions like who is maintaining it? Who is responsible for it? I don't have money to help with that or I don't have time to do that. What if it falls on my house? So now because of that disinvestment for so long, there's often a lot of questions and a lot of skepticism and like, what's going on here? Why are you doing this? And so it does suggest that to be equitable, we need to re-introduce urban forests and street trees in these communities. But to do that, we have to really rebuild a lot of community trust as well. And so it's not in my mind why we use the word just is because it's not just going back in and planting things, but it's also rebuilding relationships and trust through community work.

Comparing neighborhoods with low and high amounts of tree cover

Imagery 2023 Google, Landsat / Copernicus, NOAA, Imagery 2023 CNES / Airbus, Maxar Technologies, Sanborn, U.S. Geological Survey, USDA/FPAC/GEO, Map data 2023 Google

HOST: Could you give some examples about how you plan to, moving forward, or how you have worked with communities in this project?

TF: Sure. We're in the process of beginning to work with communities. And so to date, we worked a lot on the just understanding and describing the urban forest. Digging through all the policies and planning documents to get a handle on what has been done. Then, moving forward, we're going to work with two, possibly three different sort of collections of community groups. One being the non-profits, the city government, and the entities that helped create this plan. To understand how it's going, how it's working, what are the barriers they see? What are they doing for climate change and biodiversity? And if there's any sort of adaptations that they would want to do with the plan and sort of dig into why. The other group we want to work with is the designers and planners that are in the private sector or outside of the urban forest planning group. That's the best way I guess to put it. Because we want to know what are their thoughts on it? How are they managing, designing, and planning for climate change and urban forests? And sort of seeing if the two match up. Seeing where there are gaps or barriers. Some of them, reading through plans and things we've done so far, could be a client has a certain aesthetic vision and they like certain plants, and so they only want certain trees planted, even though they have too many of them in the neighborhood already. That we would imagine might be an example of one barrier that we would get from that group that we wouldn't necessarily get from the people writing the sort of the city-level planning documents and information. The third group are residents because of issues like what happened in Detroit, we want to know their thoughts on the tree plan, as well as what are their concerns and barriers, and information. Because Pittsburgh is unique in the sense that it's a consortium that has this put this plan together. And it's a consortium led by a Tree Pittsburgh that often does a lot of the planting and education and information around the urban forest. Whereas say a city like New York City, that's part of the city government, official part of the city government. So this is more of a non-profit public-private partnership. And they do a lot of their plantings in that way. So we wanted to see sort of these two or three groups and how they navigate that.

HOST: Alright, so I read a bit about your results, at least you're NASA-funded project. And that is related to this seed grant, correct?

TF: Yeah. There's a lot of future projects that could roll out of this and this one has helped with that one as well. And so, yeah, so Mehdi and I and some of his colleagues at Hunter College in New York, I'll have to give credit to Mehdi. He's made a lot of connections with the New York City Mayor's office. And I believe it's Jersey City in New Jersey. And a lot of different community advocacy groups that are working on urban heat island and both locations. New York City has a lot of metrics and policies in place to increase urban tree canopy, cool roofs, which is another mechanism to cool urban heat environments. But the question is, you know, we're not exactly sure how we're doing. And so we're, we're measuring that. But again, sort of leveraging what we're learning here to expand that beyond just urban forests, but other, other ways to cool the urban environment and begin to build out more focused or targeted policies or places for intervention. Particularly in gearing it towards the most vulnerable. Of all of New York City, where would investment and cool roofs and trees have the largest impact? And so we're extending the work here in a number of ways in that project. Ultimately, we do want to expand to other cities. So that's another future project because as I mentioned, Pittsburgh is unique. It has a public-private, non-profit partnership that's managing and planning, and maintaining the urban forest. We're comparing that to say, New York City has a lot of different resources, and they function differently. It's official. There are some that are private or they're not addressing it at all. And so we'd love to sort of compare biodiversity, urban forests gain or loss, comparing the different approaches to how you manage and plan for it or maintain it. And then at the very end, I would love to have a data portal, or an analysis port or a dashboard, if you will, that allows homeowners, policymakers, city officials, designers, property managers, that if they're interested in these sorts of issues, they could begin to identify where they live and say, hey, I'm interested in a tree. And so they might click there and then it produces some information not just about the benefits of trees, but recommendations even of, oh, well, we notice you live in this neighborhood. And this neighborhood already has a biodiversity issues. So please don't plant these trees. Because we want to maintain a healthy forest. Because I think some of the reasons we run into those traps, particularly as a designer. As we just don't know, sometimes. We don't know what's around us. We can only look out so far. We often for every project, can't survey the whole neighborhood. And having something like that available, I think would make decision-making at a range of levels from the individual to community or city just a little bit easier.

HOST: Thanks Travis, for spending time on Growing Impact and talking about your research.

TF: Thanks, Kevin. Thanks for having me. And if anyone should have any questions or would like to follow up with me, feel free to reach out.

This has been season 3, episode 9 of Growing Impact. To read the transcript from this episode and see images of cities before and after trees, visit the IEE website by going to iee.psu.edu/podcast. While you are there, you can also learn more about Travis and his research team, find previous podcast episodes, related graphics, and much, much more. Just visit iee.psu.edu/podcast. Thanks for listening.

Justine Lindemann

Mehdi Heris