As the United States and other countries around the world wrestle with climate change and its impacts, there is also a lot of debate related to the technology, finances, regulations, and social acceptance of potential solutions to climate change. Hannah Wiseman, an IEE faculty member and professor of law at Penn State Law, provides an overview of the legal, policy, and social complexities related to climate change solutions.

What will it mean for the U.S. if we get serious about climate change?

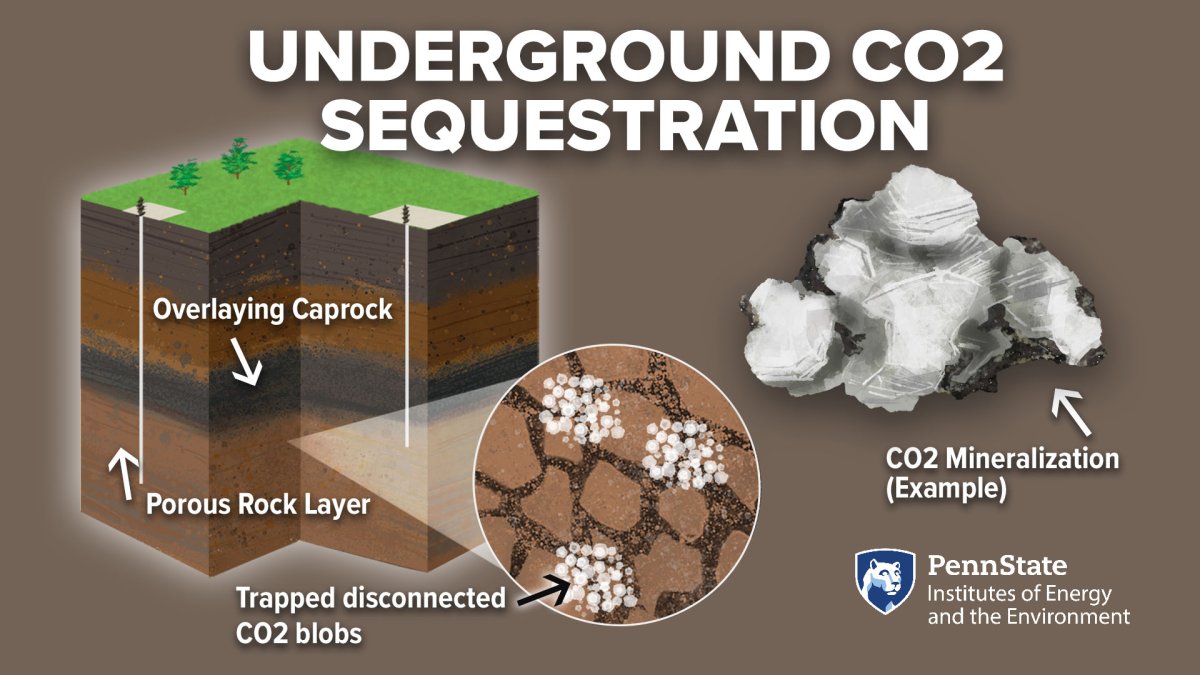

Climate change poses one of the greatest modern challenges to human well-being, the environment, and global security. To avoid potentially catastrophic effects of climate change, such as large wildfires, drought, and rapidly melting glaciers, we need to quickly and rapidly reduce emissions. This has been shown time and time again in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, which are reviewed and approved, line-by-line, by governments around the world. The scientific consensus now is we not only need to mitigate emissions, but we need negative emissions. That means we need to both, first stop emitting and second, remove carbon and other greenhouse gases from the air and store them somewhere, such as in geologic formations underground. This will require what some have termed an “all of the above” or “every technology possible” strategy. And this, in turn, requires compromise, and it requires activities that humans will naturally dislike because emissions mitigation, removal, and storage technologies are industrial-scale operations.

Among other approaches, we need to move from burning coal and natural gas in power plants to building big wind and solar farms. And we need to move from getting oil and gas out of the ground to, instead, injecting stuff underground, specifically carbon. All of those things require large amounts of land, and some are classic “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) targets—projects that individuals tend to oppose for aesthetic and other reasons.

What challenges does the U.S. face in moving toward renewable energy?

I think that policy is one of the biggest challenges to this move toward massive industrial change because policy tends to slow down development of all types of industrial-scale projects—including those that address climate change. We've heard this for years from companies building natural gas pipelines or carbon-intensive infrastructure. Now it’s occurring in the renewable energy space.

The biggest blockades to development right now are environmental review requirements and environmental laws, as well as land use regulations. This is somewhat ironic, in that the greatest threat to the environment is climate change. There's the federal National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. Anytime the federal government is involved with the project, which is common because there's federal funding or federal lands involved, there must be extensive review of the environmental impacts of that project.

Then there are all the wildlife statutes. These are some of the strongest federal environmental policies. For example, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act provides very strong protections for all migrating birds, and the Endangered Species Act covers any jeopardized animals or plants listed as endangered by the Federal Fish and Wildlife Service. This has been an ongoing challenge for wind farms and other forms of development.

With respect to land use regulation, citizens groups, some industry actors, and local and state governments are blocking numerous solar farms and transmission lines for zero-carbon energy projects. There is also growing opposition to carbon capture and storage projects (CCS).

There are important reasons for land use regulations, environmental review, and wildlife statutes, but we need to consider how we might amend these requirements so that we can still respect these important values and move forward with efforts to address climate change.

What should people consider when weighing climate inaction against climate solutions that could cause unforeseen problems?

As we move toward more negative-carbon projects, I have heard growing concerns from environmental groups and environmental law professors about the risks of carbon injection. My worry is that these concerns about potential risks of negative-carbon technologies might overshadow consideration of the risks of climate inaction. So, we need to think about the risk of doing nothing as compared to the risk of the negative-carbon projects. Let's do the best we can with carbon injection. Let's address potential risks such as leakage or seismicity. But in my view, I don't think we should let concerns about leakage or seismicity block or substantially slow down these projects, because the cost of inaction is quite high.

Why is it difficult to agree on solutions for energy and climate change?

Humans tend to look for silver bullet solutions and so far, there really is not such a solution when it comes to zero-carbon energy. That's why we shouldn’t throw all of our money into one technology. My students will sometimes say, why are we not taking these billions of dollars from the Inflation Reduction Act and putting them all toward nuclear energy, for example. We will certainly need nuclear power as one of the zero-carbon technologies moving forward, but there are also downsides, such as cost and waste disposal. Nuclear power plants are very expensive, and we have not been able to build a high-level centralized nuclear waste repository in the United States.

It's the same with wind and solar energy. They're an important solution, but they're very land intensive. If we want to go to zero-carbon with just wind and solar (or wind, solar and geothermal), this infrastructure (plus transmission) will occupy somewhere between 14 and 16 million acres (about the area of West Virginia) of land plus perhaps some offshore space. Humans understandably object to changes to landscapes—and the view from their backyards.

Each solution has its downsides. That's why we need a diversity or portfolio approaches.

What do you foresee occurring in the legal space with new technologies?

Some of the new zero- or negative-carbon technologies are going to require many laws and policies to change because we have not done them on a commercial scale before. That's particularly true for geologic carbon sequestration—storage of CO2 in rock formations underground. We don't have a fully developed legal regime for the subsurface of the earth. It's kind of the wild west. We have been using the subsurface for a very long time. There are hundreds of thousands of injection wells already for liquid waste, and almost a million active oil and gas wells. But we haven't been using the subsurface at the scale of carbon injection, where you can have carbon migrating underground hundreds of miles. That is a vast use of the subsurface, and it will require changes to land use, planning, underground property rights, and the statutes that address any risks underground.

Does the structure of government in the U.S. complicate energy development?

Right now, the assumption is that we're going to be doubling or tripling the amount of transmission lines in the United States, building millions of new acres of solar (and some wind) farms, and injecting carbon into huge storage fields, which are massive endeavors. However, these activities are largely regulated on a state-by-state or even local government basis, which means that states or municipalities can—and often do—just block them. There will need to be some cooperative federal-state regime for siting or locating these transmission lines, with adequate voice for state and local concerns. A similar regime might be needed for carbon storage. For renewable energy siting, state-local regimes that prevent full local bans on renewable energy might be needed. Congress has taken very small steps toward federal control over transmission line siting. But there's not really a feasible policy solution in place yet.

The federalist system in the United States—which gives states and local governments most control over the location of energy resources and transmission—is a major challenge to energy development. It's also important, though, because it has allowed for important zero-carbon innovations. Most of the zero-carbon efforts that have occurred in the United States until the last few years have been led by state and local governments. The federalist system has value, but it's messy and complex. We need to consider how we can arrange all of these messy actors and move them forward toward a national mission.