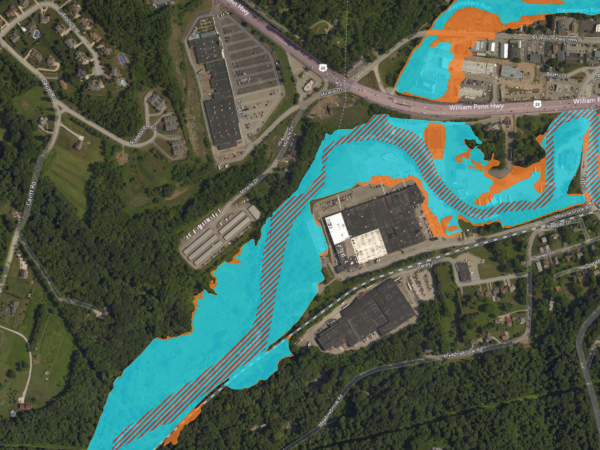

Flood damage remains the costliest type of disaster across the globe, and the United States experiences considerable risk with over 250,000 rivers and streams and 3.5 million miles of shoreline. Hurricanes and super storms regularly cause serious damage in the Gulf and Atlantic coast states, and millions of Americans live in a flood plain with at least a 1% chance of flooding annually. Climate change and sea level rise will likely increase the probability of such flooding.

While some coastal housing may be owned by wealthier individuals, riverine flood plains are dominated by low-income housing, and the unequal impact of flood damage raises considerable environmental justice questions. Beyond the tragic loss of life, flooding may affect long-term health (physical and psychological), education, property values, and impacts on public finance (which can then indirectly cause long-term effects for citizens in those communities). Capacities for adapting to and mitigating the flood risks –at household and community levels –differ markedly by income, race and ethnicity, age, and other factors that vary with vulnerabilities.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) regulates and backs flood insurance for property owners, and FEMA has a role in mitigating flood damage, but decisions on zoning, development, infrastructure, and ex ante mitigation are made at the local and state levels. The burdens of ex ante flood mitigation can be substantial for the public and private sectors, limit economic growth, and impinge individual liberties. Further, elected officials may pay an electoral price for failure to act if a disaster occurs, but the political calculus weighing the ex-ante burden of flood mitigation against the potential long-term ex post benefits of damage averted is difficult. To encourage local governments to adopt mitigation efforts, Congress created the Community Rating System (CRS), which awards points for different actions, and property owners in those communities receive discounts on their flood insurance in proportion to the CRS level.

We build on previous research by two of the team members that included CRS scores, demographic data for communities, housing values, previous flood damage, public finance, and weather data at aggregated levels such as census tracts, cities or counties. We seek to use individual level data to gain a better understanding of the social effects associated with flooding and development in flood zones, such as whether racial/ethnic minorities, children, and those with low income suffered the most, which aggregate data studies cannot adequately address.

We seek to create a novel individual-level dataset that combines flood, demographic, mortgage, and property data, including flood data from the First Street Foundation (FSF) and individual-level data from CoreLogic. FSF has created a dataset of flood history and flood risk scores for most properties in the US. The results reveal greater risk for more properties than existing NFIP flood maps, and the distribution suggests even greater social injustices. CoreLogic has data on mortgages, tax assessments, building features, and demographics of hundreds of millions of Americans. Additionally, voter registration and Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data can enhance the demographic information for those missing observations in the CoreLogic data. The merger of these datasets with address information would allow further mergers with public finance, municipal political structure, census, and CRS data sets to help assess impacts on communities.

Researchers

Heather Randell

Doug Noonan