Tackling climate change is a major challenge to policy makers around the world. To assist climate policy making, the research community has developed a powerful set of tools to combine insights from economics, technology, and climate science. These detailed process-based integrated assessment models (IAMs) have examined cost-effective pathways that could avoid the consequences of climate change and identified key sectors and technologies that will be critical to achieve deep decarbonization.

However, these tools miss a crucial factor that shapes climate policy in the real world: Politics. The IAMs are often inadequate in characterizing the difficult trade-offs faced by politicians and investors. For example, how to gather public support for climate policy when many households rely on fossil fuel industries for their livelihoods? How to boost investments in breakthrough clean energy technologies when many investors still view these ventures as too risky?

We need models that can do a better job of representing how humans and institutions behave in the real world where social and political factors often lead to outcomes that deviate from economically optimal pathways.

Bringing together IAM modelers and political scientists, we identified eight political insights that are important for the success of real-world climate policy:

- Access to capital for clean energy investments can be constrained by risk-averse investors who fear unpredictable changes in policy.

- The choice of policy instruments, such as whether to subsidize green technologies or tax polluting industries, can be influenced by which interest groups are mobilized.

- Stranding of fossil-based energy assets might limit the degree to which emissions can deviate from their previous trajectory. (Stranded assets are fossil fuel supply and generation resources that lose their value as a result of the transition to a low-carbon economy.)

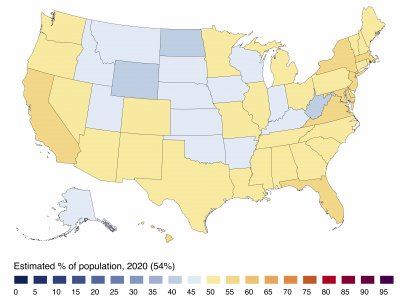

- Unequal costs and benefits on different economic and racial groups can affect policies’ political acceptability.

- Public opinion might facilitate stronger action to tackle climate change.

- Confidence in political institutions can influence the public’s willingness to support climate policy.

- Trade and investment policies can expand the markets for new green technology, leading to lower costs and more political support.

- Competence of government influences a state’s ability to intervene in markets, make choices and alter the cost of deploying capital.

We then assessed eleven model improvements to represent these political insights, ranging from adding new factors in functions or computing at different geographical resolutions, to including new data sets. For each, we evaluated how much the model improvement might add value for decision makers, and the feasibility of implementing it.

We highlighted two key considerations to improve IAMs.

First, model improvements are only worth the effort if they help decision makers, and the right choices depend on the audience. A negotiator at the United Nations Climate Change Conference might want to understand how international trade policies affect global emissions. A national policymaker, however, might need to balance attempts to decarbonize transport infrastructure against election promises they have made to car-factory workers in their constituency. This means moving away from jack-of-all-trades models and towards a suite of tailored ones, each tuned to a specific purpose and audience.

Second, success will require new transdisciplinary collaborations. We will need teams of scholars who are anchored in the IAMs (with knowledge about what is feasible) and tethered to the social sciences (aware of what is important).

Reference:

Peng, W.; Iyer, G.; Bosetti, V.; Chaturvedi, V.; Edmonds, J.; Fawcett, A.; Hallegatte, S.; Victor, D.; van Vuuren, D.; Weyant, J. Climate Policy Models need to Get Real about People – Here’s how. Nature 2021, 594, 174-176. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01500-2