The smoke alarms in the airplane went off as my brother and his young family returned home to LA from their wintery New England holiday. Plumes of smoke could be seen swirling around the hills they’ve known for decades as home. Already cautious of flying, now they were cautious of landing in the firestorm that was sweeping through the City of Angels. His family was ultimately spared the worst, but their community is devastated.

Fires out of sync with nature's cycles

While fire is a natural part of healthy ecosystems across much of the Western U.S., these fires are unnatural and out-of-sync with the natural cycles of death and rebirth inherent to environmental systems. Even before these LA fires, 15 of the last 20 most destructive fires happened in California within the last decade. The 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise killed 85 people and destroyed over 18,000 structures. The August Complex in 2020 consumed over 1 million acres and turned San Francisco into a vision of the apocalypse. The LA fires are set to become the most expensive in California’s history. Across North America, wildfires are larger, more severe, and moving faster. Unhealthy air is affecting hundreds of millions of people annually, with children more than 10 times as likely to suffer respiratory harm.

Is climate change to blame?

Is climate change to blame? The answer, simply, is yes. But we still have time.

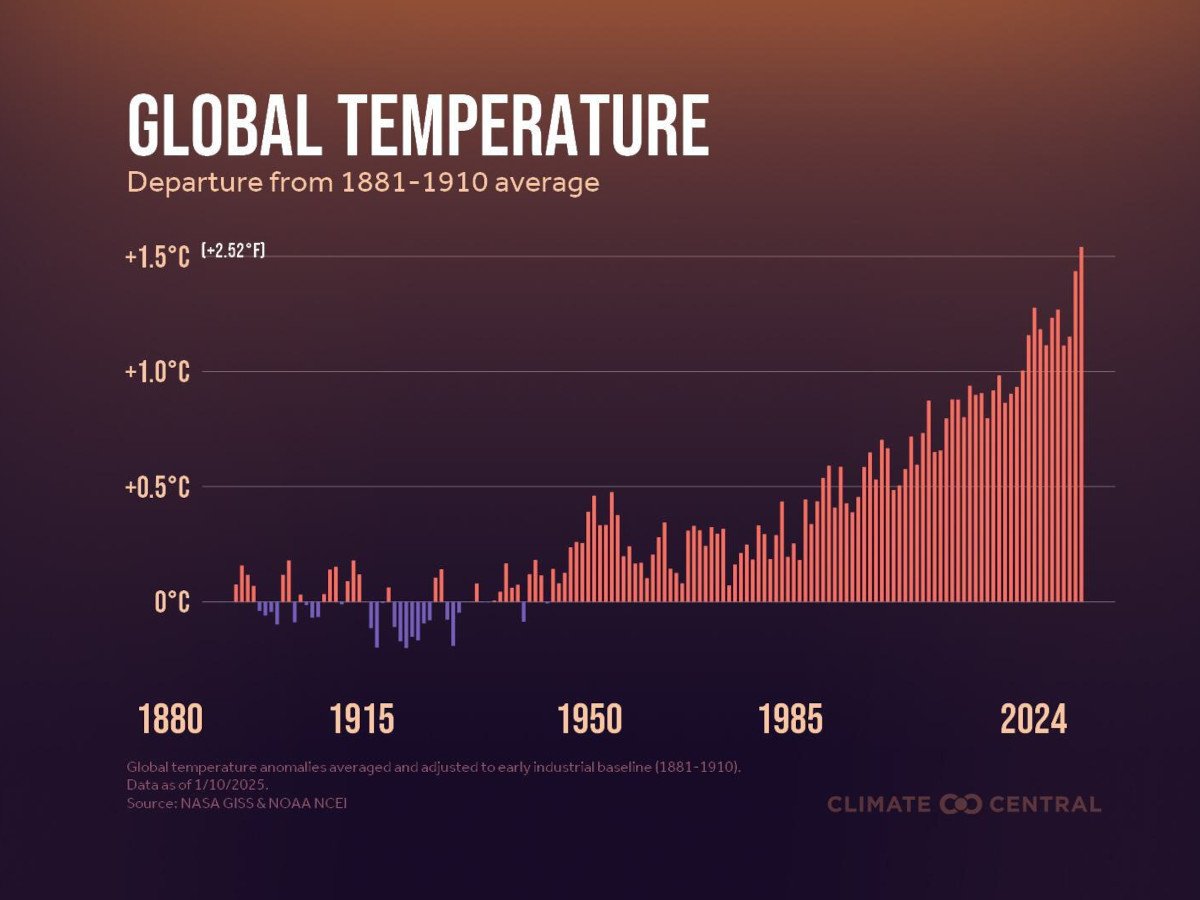

Since Prometheus stole the gift of fire from Zeus and delivered it to humans, we have struggled to reconcile the revitalizing and destructive power of the flame. We understand that decades of fire suppression, invasive species, the eradication of cultural burning practices, and the tight intermingling of humans and fire-prone ecosystems, have fundamentally shifted the equation. But the evidence connecting extreme wildfires to a changing climate is clear. 2024 is now confirmed as the hottest year on record, and the 10 warmest years since 1850 have all occurred in the past decade (yes, that means every year is one of the hottest). Reduced snowpack, longer and more severe droughts, and greater evaporative demand mean that fuels are drier and more combustible. The ebbs and flows of atmospheric circulation patterns are more erratic. They stall, causing “heat domes” that created the conditions for the 2023 Canadian fires that resulted in smoke blanketing the Eastern U.S. They intensify, creating steep gradients between high- and low-pressure systems, amplifying extreme winds, like Santa Ana, and increasing risks for lightning.

Wildfire risk in Southern California is far from new, but the rules are changing. After an extended extreme drought period, California enjoyed a few wet years (relatively speaking), contributing to fuel build-up. Then, this year, Southern California again dried, experiencing only a fifth of an inch since July. While gusty Santa Ana winds are a regular feature of the Southern California wildfire season, this year, they raged, pulling in dry air from the Great Basin and sucking vegetation even drier. While we don't currently know the exact ignition source of these fires (downed electricity lines? hopefully not arson), what is clear is that the fan that fueled these flames was in hyperdrive, affecting an already vulnerable ecosystem.

Solutions: What's next, and what can we do?

What was once unthinkable (a major US city burning) is now reality. If LA can burn so devastatingly, what’s next, and what can we do?

First, we need to make the connection between our highly consumptive lifestyles and greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels. Science tells us that every amount of fossil fuel emissions reduction will help reduce extreme events in the future. Luckily, this doesn’t mean we have to give up our comforts. The renewable energy industry grew 50% in 2023 and is likely to double or triple by 2030 with sustained investment.

Second, we need to support healthy forest management with resources to protect and conserve sensitive and critical ecosystems, scale beneficial fire use to mitigate risks, especially near human infrastructure and communities, and support societal resilience for communities affected by wildfires.

Third, we need to understand that we live in the Pyrocene Era. We currently depend on the combustion of fossil fuels to fuel our livelihoods, and due to the resultant warming, wildfires, also a combustion process, may be the price we pay.

In that context, there are many ways communities and households can protect themselves proactively, such as by becoming part of a FireWise Community, with resources for education, research, and emergency preparedness.

Having studied wildfires my entire career, I never thought I would be worried about my brother living in central LA. I never thought, living in Pennsylvania, that wildfires were part of my personal climate-risk calculator, but then drought in Appalachia and New England caused unprecedented wildfires this fall, too.

Hope for the future

The good news is that we are talking about it, the first step towards action.

Despite the daunting challenges posed by climate change, we are not powerless. Communities across the world are stepping up to meet the moment, embracing renewable energy, sustainable living, and proactive fire management. We’re learning to adapt, innovate, and protect what we cherish. Every conversation matters, every action counts, and it’s never too late to make a difference.

LA will rebuild, as it always has, and with collective effort, we can forge a future where such devastating fires become less frequent.

There’s still hope—and it lives in the choices we make today. Together, we can shape a safer, more resilient tomorrow.

Erica Smithwick is a distinguished professor of geography with expertise in landscape and ecosystem ecology and wildfires. She is also an associate director of the Institute of Energy and the Environment and the director of the Penn State Climate Consortium. Her research focuses on how disturbances, especially fire, affect ecosystem function and socio-ecological resilience, with emphasis on protected areas in Africa and the U.S.

Cover image credit: California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) CC BY-NC 2.0.