Harnessing the power of the sun provides an exciting alternative to reliance on fossil fuels. Over recent years, solar energy has become more affordable and widely available. This is largely due to the increasing efficiency of solar panels and growing markets for solar panel materials. Yet, its development requires large areas of land that are often in competition with agricultural, industrial, or residential uses, and this competition makes solar expansion complex.

Pennsylvania is becoming a hot spot for solar energy, particularly after the release of the Pennsylvania's Solar Future Plan in November of 2018. This plan declared a goal to increase in-state solar energy generation to 10%—up from the state's current solar energy generation of less than 1%—which will generate 10–12 gigawatts by 2030, initiating a rapid increase in solar capacity across the state.

Farmland is a prime place for this expansion to occur in Pennsylvania. The land is flat, well-drained, sunny, and often close to infrastructure like transmission lines or substations. But there is conflict in rural communities about using the land for solar energy, particularly over how it benefits rural communities and concerns over loss of productive farmland for up to 30 years, the average length of a solar land lease.

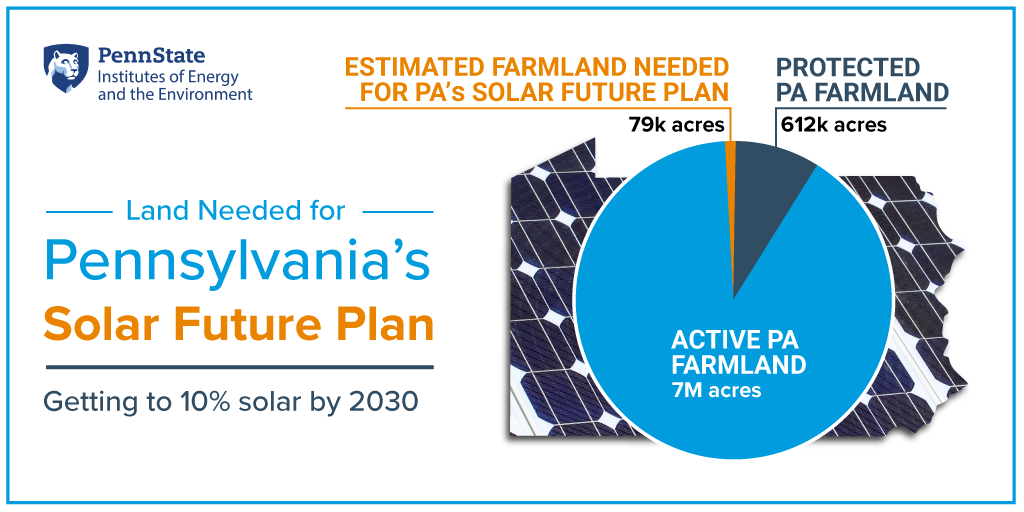

According to economic modeling through the PA Solar Future Plan, there are two scenarios to achieve the 10% goal by 2030. Scenario A would use 89 square miles or 56,800 acres of farmland to meet its goal. Scenario B would use 124 square miles or 79,200 acres of farmland. For perspective, the city limits of Philadelphia measure 141 square miles or 90,690 acres.

So, if all grid-scale solar was placed solely on farmland in Pennsylvania, it would only comprise 0.8% and 1.1% of total operated farmland for Scenarios A and B respectively, and this would not include other types of land, such as abandoned mine lands, forested lands, and other open, marginal land. Nonetheless, the loss of historic farmland and its social, cultural, and ecological value is a prime concern for rural PA communities and one that requires increasing attention.

I am a part of a research team that explores the localized realities of solar energy expansion on agricultural land in southeastern Pennsylvania. Our project addresses gaps in understanding of how agricultural landowners navigate the ethical and logistical tensions of using their land for solar energy production. It also investigates how such projects impact their broader communities and landscapes. We ask questions such as:

- What are the ecological, economic, and social tradeoffs associated with using agricultural land for solar energy expansion; and

- What are the energy justice implications of these tradeoffs?

We find that farmers enter solar leases for a variety of reasons. These include financial gain due to the high margin for profit compared to traditional crop production, keeping their farms in the family for future generations, protecting land from industrial development, and letting their land “rest” for the length of the lease to restore soil quality. As farmers navigate these priorities, they must also work with an attorney to ensure their lease provisions are fair and flexible for years to come without losing the “privilege” of the lease itself. Moreover, farmers often sign a non-disclosure agreement during these negotiation processes, making it difficult or potentially illegal to discuss these provisions with other farmers or community members until the contract is finalized. Agrivoltaics – or the co-location of crop production, grazing, or pollinator-friendly plants with solar panels – is difficult for farmers and developers alike to implement because incentives in a solar lease for this type of land management are either vague or absent altogether. This lack of transparency and community involvement in these leasing processes, as well as a need for increasing solar education, contributes to strong community opposition for on-farm solar, making its expansion potentially polarizing for local communities.

Energy transitions must be oriented toward the local community’s needs and preferences and mitigate further harm in the context of climate change. The current and future expansion of solar energy in Pennsylvania highlights the importance of doing things differently than the expansion of Marcellus Shale natural gas production. Through this research and engagement, we can learn from prior mistakes made during the shale gas expansion to make sure solar moves forward in a more sustainable and equitable way.

Kaitlyn Spangler is a postdoctoral researcher working in the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences. She is a human-environment geographer whose research works toward building more sustainable and diversified working landscapes and, therein, equitable and just climate change solutions.