In February 2021, a cold snap hit the Southwest U.S., causing Texas to experience a deep freeze. Sustained below-freezing temperatures disrupted electricity and natural gas services, primarily due to frozen equipment and a dramatic surge in energy demand for heating, leaving more than 4.5 million homes and businesses without power.

Such extreme weather events challenge the reliability of electric power systems as the energy resource mix evolves, underscoring the need for sufficient resources to meet electricity demand at all times. To address this, U.S. electricity markets have implemented various mechanisms to ensure resource adequacy. Through laboratory experiments, we compare three market structures—a market with a capacity market mechanism, a market with a scarcity pricing mechanism, and an energy-only market—to examine which best encourages investment in generation capacity and reduces unserved demand.

What is resource adequacy, and how does it link to the reliability of electric power systems?

Resource adequacy refers to having sufficient generation resources to meet electricity demand at all times, including during periods of peak usage. This standard typically assumes that capacity shortfalls should occur no more than one day every ten years. Recent scarcity events in the United States highlight that reliability challenges in renewable- and gas-dominated electric power systems often arise not from a lack of generation capacity to meet peak demand but from insufficient available capacity to provide electricity when needed. Wholesale electricity markets frequently fail to encourage adequate investments in generation capacity due to market imperfections that suppress prices, leading to insufficient revenues. This phenomenon, often called the “missing money” problem, threatens system reliability by deterring investment in necessary resources.

What are the factors that lead to the “missing money” problem in electricity markets, resulting in potential underinvestment in generation resources?

Two primary factors contribute to the “missing money” problem in electricity markets. First, price caps, often set by Independent System Operators (ISOs) to prevent price spikes and protect consumers from market abuse, limit electricity prices during scarcity periods. These caps are typically lower than what consumers might be willing to pay to avoid power outages, preventing prices from reaching levels necessary to encourage investment. Second, system operators frequently take out-of-market actions to maintain grid reliability during high demand. Actions like dispatching resources outside the economic merit order distort price signals and further suppress market prices. Together, these factors reduce supplier revenues during scarcity conditions, hindering future investments in generation resources.

What mechanisms are currently used in U.S. electricity markets to ensure resource adequacy?

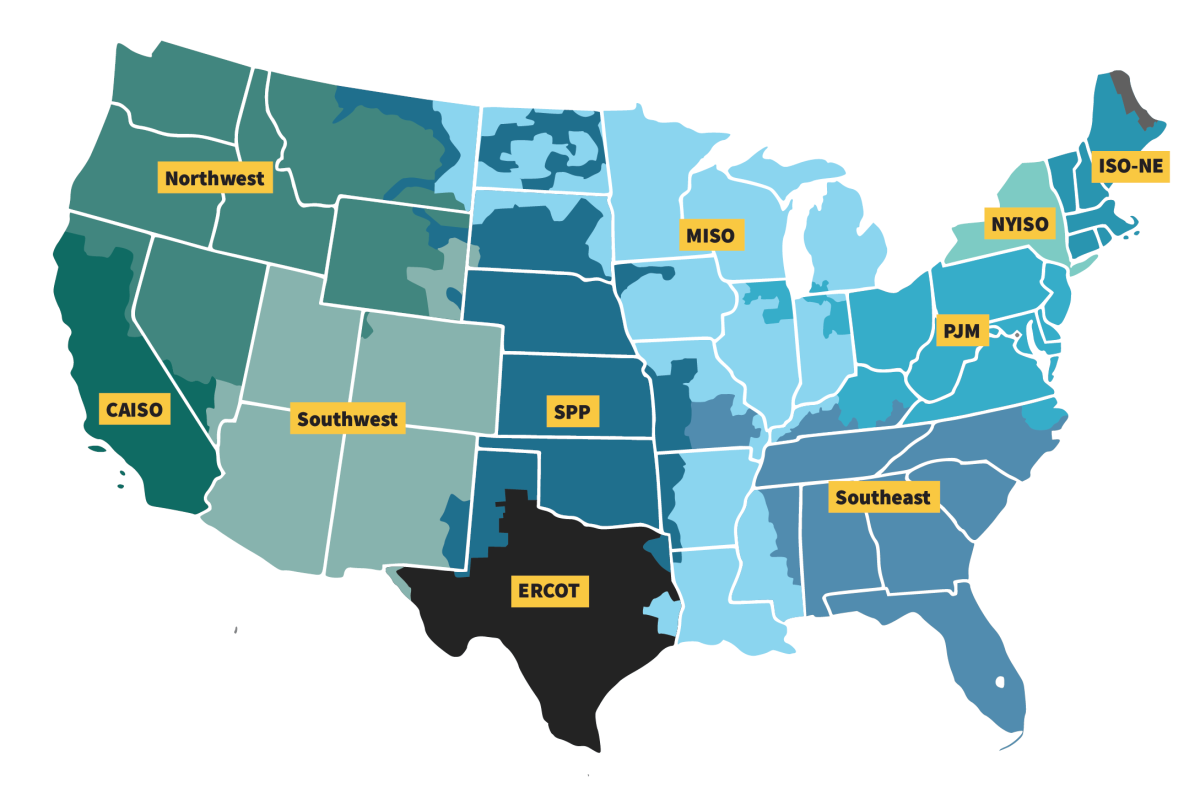

U.S. electricity markets use two primary mechanisms to guide investment decisions and compensate generation companies: capacity markets and scarcity pricing.

The capacity market, adopted by ISOs such as PJM, ISO-NE, NYISO, and MISO, operates ahead of energy markets and procures capacity through centralized auctions. Suppliers earn market-based payments determined by bids and a capacity demand curve. These payments, combined with revenues from energy and ancillary services markets, help companies recover fixed costs.

In contrast, ERCOT employs scarcity pricing. Here, companies earn additional revenues by providing reserves—unused capacity that serves as backup resources after meeting electricity demand. An operating reserve demand curve in the real-time market determines reserve prices based on system reserves. These reserve prices are added to electricity prices, creating financial incentives for investment.

The distinction between these mechanisms lies in their compensation structures: capacity markets guarantee upfront payments, while scarcity pricing relies on price spikes during scarcity conditions. This difference affects how generation companies perceive risks and uncertainties, with capacity markets offering more predictable returns and scarcity pricing markets introducing greater volatility.

| Feature | Energy-Only Market | Scarcity Pricing Market | Capacity Market |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investment Incentive | Revenues from electricity sales only | Revenues from electricity sales + high prices during scarcity events | Revenues from electricity sales + upfront capacity payments |

| Price Signals | Price caps can suppress market prices, leading to insufficient payments for fixed cost recovery | Unanticipated price spikes during scarcity ex post | Guaranteed capacity payments ex ante |

| Investment Risk | Relies solely on electricity prices | Potential for high rewards during scarcity, but uncertain | Guaranteed capacity payments reduce risk |

| Impact on Generation Capacity | Potentially underinvests; "missing money" problem | Can incentivize investment, but may not yield the right capacity types and amounts, nor guarantee energy availability when needed | Can incentivize investment with potential overinvestment, but may not yield the right capacity types and amounts, nor guarantee energy availability when needed |

| Examples | Australia, Alberta (Canada), and New Zealand | ERCOT (Texas) | PJM, ISO-NE, NYISO, MISO |

What makes laboratory experiments a valuable approach for comparing electricity market structures, and why do they provide complementary insights that differ from traditional modeling?

Traditional numerical models, such as optimization and equilibrium models, have limitations due to their reliance on assumptions and simulations. Laboratory experiments, by contrast, allow researchers to observe real human decision-making in simplified but realistic market settings. This method enables a direct comparison of market structures under controlled parameters that would be difficult to replicate in natural settings.

In our study, equilibrium models provide predictions for subject behavior, which we then compare to observed behaviors in experiments.

The experiments were conducted virtually with 160 student participants recruited through the Online Recruitment System for Economic Experiments (ORSEE.3) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Participants acted as generation companies, making capacity investment decisions under each market structure. They were compensated based on profits earned, ensuring realistic incentives. To ensure participants understood the instructions, we included quizzes and practice rounds before the experiments began.

How do market structures compare in your laboratory experiments?

The experiments compared three market structures—energy-only, scarcity pricing, and capacity markets—to assess their ability to attract investment and meet electricity demand. Subjects made capacity investment decisions at the start of each experimental day and competed to meet electricity demand across three periods with varying demand levels (low, medium, and high).

In the energy-only market, companies relied solely on electricity revenues to cover costs. In the scarcity pricing market, unused capacity after satisfying electricity demand could be sold as reserves for additional revenue. In the capacity market, companies received upfront capacity payments along with electricity revenues to remunerate investments.

Experimental results confirmed that the energy-only market produced the lowest level of capacity investment, insufficient to meet peak electricity demand. The capacity market led to higher investment levels compared to scarcity pricing, reducing electricity shortages across demand scenarios. However, neither market fully met peak demand, and investment levels fell short of model predictions. Despite these shortcomings, both scarcity pricing and capacity markets effectively reduced unserved demand. Interestingly, there was no statistically significant difference between the two mechanisms in mitigating shortages during peak periods.

Chiara Lo Prete is an associate professor of energy and minreal engineering and a faculty member of the Institute of Energy and the Environment. Her research interests include energy industry restructuring, pricing issues and market design in the United States. Her current work focuses on equilibrium models of price manipulation in multi-settlement electricity markets; optimization models for the analysis of economic, environmental and reliability impacts of microgrid penetration in power networks; economic models assessing price and welfare effects of natural gas pipeline expansion projects.

Jiaxing Wu is a Ph.D. student in the Energy, Environmental, and Food Economics Program. Her research focuses on lab experiments to compare electricity market structures and modeling of interdependent gas-electric systems.