The insect flutters her antennae to taste the egg mass beneath her, movements stuttering like stop-motion animation. She resembles a little black ant, but the scientists gathered around her know better. She is an Anastatus orientalis wasp, our potential ally in the war against spotted lanternflies.

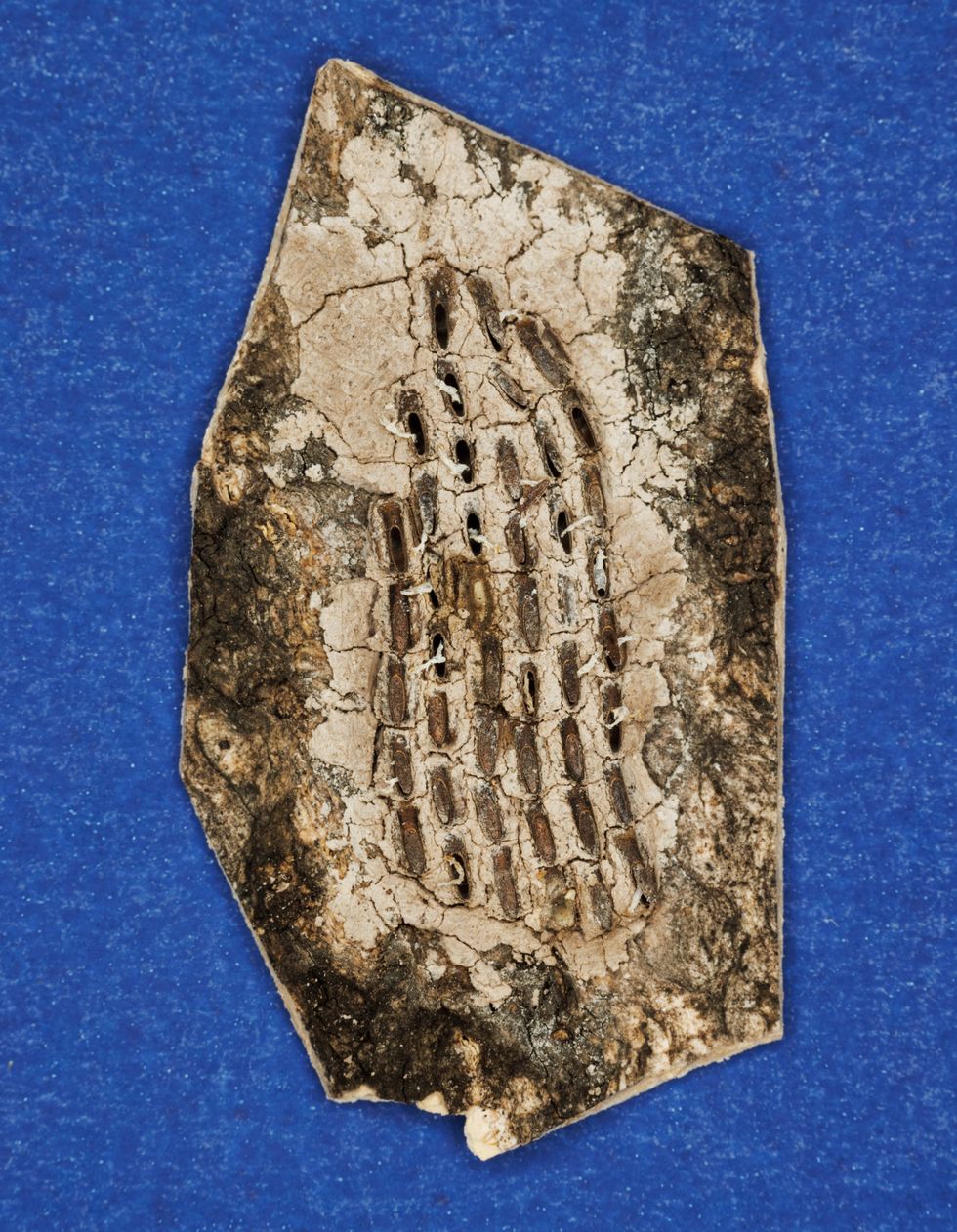

There’s nothing in her glass jar except a piece of bark that looks like it’s been smeared with spackle. Oblong shapes create hummocks beneath the coating. The wasp lifts her head and drills down with her stinger, which can taste the living goo of the insect egg it pierces. If the taste is right, she will squeeze one of her own eggs inside.

The researchers will learn in a few weeks what she decided, when the egg’s occupant emerges. If it’s one of her offspring, that’s another black mark for our alliance with her species—an alliance that’s looking increasingly shaky.

Scientists hope to partner with A. orientalis because these wasps attack spotted lanternflies, invasive pests that are spreading across the country. Spotted lanternflies are killing grapevines, bombarding homeowners on their patios, and blackening gardens with their sticky feces. No one is sure what they’ll do when they reach new areas such as California.

In their native range in China, spotted lanternflies rarely cause problems. They are kept in check by A. orientalis and another parasitic wasp called Dryinus sinicus, which is also being vetted as a potential pest-killing ally. If these wasps pass our tests, researchers will release them on American soil, sending them out to slay our lanternfly foes.

But in this sterile white room on a military base an hour southeast of Boston, the Anastatus wasp is not attacking the eggs of our enemy. Instead, she is piercing an egg laid by another type of lanternfly called Poblicia fuliginosa, which lives in winged sumac thickets in the southern U.S. If the Chinese wasps are released in the U.S., they will probably kill spotted lanternflies—but they might also kill these harmless native lanternflies and other American insects.

It’s the quandary that now faces all so-called “classical biological control” projects, efforts to control invasive pests by importing natural enemies from the pest’s native range. Biological control, also called biocontrol, has had many stunning victories, from ladybugs that saved the California citrus industry in the late 1800s to weevils that helped save the Florida Everglades from an onslaught of invasive trees a century later.

Efforts to control pests with foreign species have also backfired. Cane toads have become a plague in Australia far worse than the sugarcane-eating beetles they were supposed to control, while mongooses that were introduced to kill rats in places such as Jamaica and Fiji have instead decimated certain populations of the islands’ unique native birds.

Such disasters have inspired backlash against biocontrol, sullying its public image and spooking policymakers. The path to releasing a foreign species now snakes up mountains of requirements meant to ensure that the creature being deployed won’t harm anything but the pest it is aimed at.

The scientists who work on biocontrol climb those mountains willingly. They know what’s at stake better than anyone else. The native Poblicia eggs that the wasp is probing in her jar come from a colony bred for the purpose by Tyler Hagerty, a University of Delaware graduate student who is working on spotted lanternfly biocontrol. Before Hagerty started collecting and raising the mottled gray-black insects, no one even knew what their eggs looked like.

“I love those little lanternflies to death,” says Hagerty. “Even if it’s a little bug that nobody really knows of, it’s still worth studying, worth understanding, and definitely worth not putting in the path of danger.”

No matter how much data the researchers gather, they still won’t know for sure what the wasps will do once released. Eventually, experts and regulators must make a decision anyway. They will weigh the threat of spotted lanternflies against the lives of native insects and the choices of thousands of wasps in glass jars, and they will judge: Is it worth the risk?

The Pest

Early reporting painted spotted lanternflies as a doomsday bug. Researchers knew the insects could feed on more than 70 types of plants in addition to their primary food, the tree of heaven. The potential lanternfly buffet included food crops such as apples and peaches and timber trees such as oaks and maples. No one knew how much the insects would eat.

“What was really scary about it was the number of different industries that were potentially impacted,” says Julie Urban, PhD, an evolutionary biologist at The Pennsylvania State University who is studying the lanternfly invasion. Now, nine years after spotted lanternflies were first found in the U.S., those fears are starting to look overblown—but that could still change as they continue to spread and long-term impacts reveal themselves. The pests and their eggs frequently hitchhike on human vehicles and cargo, and they are now found in 14 states, including most of the mid-Atlantic region and parts of the Northeast and Midwest.

For the average homeowner, the bugs are annoying. They don’t bite or sting, but their sugary poop attracts stinging insects. As it builds up, it grows black fungus called sooty mold that makes vegetation look scorched.

Spotted lanternflies cause stress to certain trees such as red maples, but the only crops they have really damaged are grapes. Pennsylvania and surrounding states where the lanternflies have spread are dotted with small, family-owned vineyards and wineries. In a few cases, swathes of grapevines died when the lanternflies moved in. Most grape growers have been able to maintain their harvests, but they must now douse their vines with insecticides.

Ben Cody launched 1723 Vineyard and Wineries with his wife Sarah Daily in southeastern Pennsylvania in 2014. Before the lanternflies appeared in his vineyard in 2020, he sprayed insecticides at most once or twice a year, and sometimes not at all. Now he must spray insecticides five or six times a year. Afterward, dead lanternflies litter the ground beneath vines blackened by sooty mold.

Last fall, the vines closest to the forest turned yellow and red earlier than normal—a sign of mounting stress from lanternflies that migrate in from the trees. Cody fears that if the row next to the forest dies, it will be impossible for new vines to survive the yearly onslaught, and the lanternflies will keep moving deeper into the vineyard.

I ask if he would consider cutting down his forest to protect his grapes. “Yeah, I guess—maybe, probably. But I’d sure hate to do it,” he says. “It’s a really pretty old hardwood forest, and it’s never been cut, near as I can tell.”

All the grape growers I spoke with are eager for a wasp that could control spotted lanternflies without pesticides. But they share researchers’ concerns for native insects, and they support the ongoing safety testing, even though each year of research is another year they must wait before receiving the wasps’ help.

The U.S. is not the first country to face this dilemma. Spotted lanternflies invaded South Korea in 2004, a decade before they first arrived in the U.S. In response, Korean scientists did what we are now considering: They released the wasp A. orientalis.

Within a few years, spotted lanternfly populations in South Korea had dropped so much they were no longer a major problem, says Seunghwan Lee, PhD, an entomologist at Seoul National University. The lanternflies are now no worse than the many other pests that Korean farmers routinely deal with.

Lee is collaborating with USDA researchers to figure out whether the Anastatus wasps are responsible for solving the Koreans’ lanternfly problem. He says he and his colleagues have observed the wasps emerging from about 20 to 30 percent of the spotted lanternfly eggs they collect, with some areas showing parasitism rates as high as 70 percent. The work is ongoing and not yet published, but based on what he has seen so far, “this thing’s working rather well,” says Lee. He thinks it could work in North America, too.

There’s still no word on whether the wasps attack anything besides spotted lanternflies in South Korea, or even in their native China. Researchers in both countries are collecting eggs from various insects and watching to see whether A. orientalis hatches out of them.

The Wasps

Tyler Hagerty, the PhD student who raises native Poblicia lanternflies, leads me into the office he shares with master’s student Cat Williams. Hagerty and Williams are advised by professor Charles Bartlett at the University of Delaware, as well as Kim Hoelmer, former head of the USDA’s Beneficial Insects Introduction Research Unit, which is located on the same Newark campus. Plastic deli cups containing insect specimens and egg masses clutter the surfaces; a deer skull watches through a pair of blue sunglasses. Hagerty shakes a dead Anastatus wasp from its cup onto a piece of filter paper. The dead wasp looks sad and wilted. But when Hagerty transfers it to the microscope stage and gestures for me to look, a shimmering green jewel-creature leaps into focus.

Hundreds of thousands of wasp species parasitize other insects. Almost none of them sting humans. Some, like A. orientalis, attack hosts that are still in the egg; others lay their eggs in insects that are crawling or flying around. A much smaller number of fly species also lay their eggs in other insects. Many parasitic wasps are beautiful through a microscope, but they are so tiny we rarely notice them. If you examine a lampshade that hasn’t been cleaned in a while, some of those little dead gnat-like things are probably parasitic wasps, according to Joseph Kaser, PhD, another member of the lanternfly biocontrol team at the Beneficial Insects Introduction Research Unit.

Our other potential ally against spotted lanternflies, D. sinicus, is a wasp that tackles juvenile lanternflies with saber-like foreclaws, pinning its victims so it can feed on them or lay eggs inside them. “Think of a tiger, but it’s a little tiny wasp,” says Hagerty.

As the D. sinicus larva grows, it packs part of its body into an external sac that swells behind the lanternfly’s wing pad. Entomologists who spot these protrusions know at a glance that a young lanternfly has a D. sinicus larva feeding on it. The parasitized lanternfly struggles on for weeks until the wasp larva bursts through its sac and leaves to form a cocoon.

Because of their lifestyles, parasitic wasps are often viewed with horror. Charles Darwin once wrote to a friend that he could not believe a beneficent and omnipotent God would have created them. But they are stars of the biocontrol field. Pick an insect at random; chances are there are several wasps that lay eggs in them, and those wasps often have their own tiny wasp parasites.

For many groups of insects, particularly those that live exposed aboveground, it is these wasps that normally keep populations in check. Paradoxically, insecticides sometimes cause pest populations to boom because they kill off the pest’s parasites. Between 1985 and 2018, 237 arthropod species were released to control insect pests in North America and U.S. island territories; 208 of them were parasites.

A little over a quarter of those introduced parasites succeeded in reducing pest populations, according to a paper published in 2020 in the journal CAB Reviews. The benefits continue to snowball over time, since the introduced wasps (and occasionally flies) keep working with no further help from humans. In rare cases, the approach works so well that people can basically forget about the pest forever.

“Have you ever heard of the ash whitefly? Of course you haven’t. Because we solved the problem,” says Juli Gould, PhD, a researcher with the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. “We released this wasp, and it just took off like wildfire, and within a few years you never saw ash whitefly again.”

Some parasitic wasps attack many types of insects, but for biocontrol, researchers look for species that specialize on a particular type of host. The spotted lanternfly biocontrol project is one of six such projects Gould co-leads with entomologist Hannah Broadley from their lab in Massachusetts. Much of their team’s work consists of offering native insects to foreign wasps and hoping they leave them alone.

Biocontrol is not like it used to be

Biocontrol researchers weren’t always so careful. Virtually everyone now agrees that vertebrate predators like mongooses and cane toads are terrible for biocontrol because they eat whatever they can find. But in past centuries, people released these species in dozens of locations around the world.

Insects have also gone rogue after being released for biocontrol. In the late 19th century, a ladybug called the vedalia beetle performed a sensational rescue of pest-ridden citrus trees, inspiring a surge of enthusiasm for insects as biocontrol agents. For decades thereafter, state and federal agencies released virtually any potentially helpful insect they could find, ignoring the effects of those insects on the rest of the environment. When researchers released the parasitic fly Compsilura concinnata—one of dozens of species deployed against spongy moths, formerly known as gypsy moths, starting in the early 20th century—they thought it was great that the flies also attacked native insects, according to Mark Hoddle, PhD, an entomologist at the University of California Riverside. They figured the flies could use native insects to maintain their populations, “so when there was a gypsy moth outbreak, there would be basically a large standing army of parasitic flies,” says Hoddle.

That fly went on to attack giant silkmoths, a group that includes some of our largest and most beautiful moth species such as luna and cecropia moths. Now these moths are seldom seen in the northeastern U.S., and scientists think the Compsilura flies are partly to blame.

Researchers began raising alarms about such dangers in the 1980s, and the ensuing controversy changed the way biocontrol is done. Now, biocontrol projects in the U.S. require years of safety testing and a complicated approval process, complete with public comment periods and input from experts representing Canada and Mexico.

Many projects never make it that far. Gould and her colleagues spent more than two decades looking for an insect that would be safe to deploy against Asian longhorned beetles before finally giving up this past December. “There was a really good parasitoid, and it attacked everything,” says Gould. “After 20, 30 years of trying, we couldn’t find anything else.”

What do these wasps want?

The outlook isn’t great for the spotted lanternfly project, either, at least when it comes to the first wasp species, A. orientalis. Out of 36 native species Gould and her colleagues have offered to A. orientalis, the wasps laid eggs in 16, including native lanternflies and stink bugs. They also attacked giant silkmoths—the same beautiful moth species that previously fell victim to introduced parasitic flies.

The Anastatus wasps in Gould’s experiments still preferred spotted lanternflies, attacking them more than twice as often as they attacked anything else. That offers hope that they might choose spotted lanternflies in the wild, says Gould. But that assumes they will have a choice. To Gould’s surprise, when her team reared A. orientalis under conditions mimicking those of Beijing and Pennsylvania, some broods emerged at the wrong times of year. If the wasps were to emerge in summer in North America after all the spotted lanternfly eggs have hatched, they might instead attack native insects such as luna moths.

On the other side of the country, Hoddle and his team have tested Anastatus wasps from China with insects native to California and Arizona. Their results, published last February in Frontiers in Insect Science, were even more damning. Hoddle’s wasps attacked several native species at rates similar to or even higher than those for spotted lanternflies. One of the wasp’s favorite hosts was the greasewood silkmoth, a rare moth with a yellow owl-eye pattern on its soft gray wings. More than three-quarters of the greasewood silkmoth eggs in the study fell victim to Anastatus wasps, compared with only 58 percent of spotted lanternfly eggs.

That was enough to convince Hoddle to abandon A. orientalis. He can’t help but compare it to another parasitic wasp he worked on, Tamarixia radiata, which is now successfully controlling a pest called the Asian citrus psyllid in southern California. A closeup image of a tiny, demure-looking Tamarixia hovers beside Hoddle’s grizzled face as we talk over Zoom.

“Unlike Anastatus, this parasite is a very well behaved insect. It really only likes Asian citrus psyllid,” says Hoddle. “Take that experience, and then compare it to Anastatus, where basically you put any type of egg in front of it, it seems like it could be potentially vulnerable to parasitism.”

Hoddle acknowledges that the experiments he and Gould conducted were unnatural—a wasp loaded with eggs, trapped in a tiny jar with nowhere to go. Past work has shown that in those circumstances, some wasps will settle for insects they would never attack in the wild. “It might be a judgment: ‘Well, my ovaries are bursting; I’ve got to get rid of these eggs,’” says Kim Hoelmer, who now works as a consultant on the project.

That’s why the team in Newark, Delaware, is studying which scents the wasps are attracted to. Anastatus wasps locate eggs to parasitize by following scents left by their hosts’ feet and dragging bellies. If spotted lanternfly odors are the only ones the wasps care about, they might never find the eggs of silkmoths or other potential hosts.

But the project has faced challenges. When I visited the research facility in January 2023, Kaser had just received a new shipment of wasps from Gould’s team in Massachusetts, which he needed because their last colony mysteriously died. In a dimly lit hallway, he and Hagerty are swapping notes on where to collect spotted lanternfly eggs.

“Is that why they all died?” I ask. “Because you didn’t have enough egg masses for them?”

“They died because they’re testy little suckers,” says Hagerty. He had been out scraping eggs off trees all morning.

The choice no one wants to make

When I ask Hagerty how he feels about the prospect of releasing A. orientalis, he says he’s glad he doesn’t have to make the decision. It’s a sentiment I hear echoed by everyone from grape farmers to the scientists leading the project.

“I don’t make that decision ever. My job is to get the science,” says Gould. Between us, in my hands, the wasp in her jar retracts her stinger and turns to examine the other eggs. Gould and other scientists will have a say in whether to submit a petition for release, setting in motion the approval process. But the final decision belongs to many people. If it goes wrong, the entire agency will bear the blame. The USDA hasn’t given up on A. orientalis yet. It is still funding Hoelmer’s scent experiments in Delaware, as well as research to find out what wild A. orientalis are attacking in Asia and the experiments Gould and Broadley are running in Massachusetts. There are several types of A. orientalis from different parts of China, and Gould and her colleagues have completed testing on only two of them.

But that is no longer where their hopes truly lie. At meetings last December, USDA researchers and policymakers agreed to shift the bulk of their resources to the other wasp, D. sinicus—the one that hunts juvenile lanternflies with its oversize front claws.

The first step in studying any insect for biocontrol is getting it to survive and breed in the lab. That’s where the D. sinicus research has been stuck for years—but no longer. Gould beams as she opens a growth chamber that resembles a refrigerator, revealing rows of plastic vials containing D. sinicus cocoons.

D. sinicus larvae spin cocoons after crawling away from the eviscerated remains of their hosts. In some cases, the silk is translucent, revealing the developing wasps within. First, red eyespots appear; then the amorphous bodies coalesce and darken into their ferocious adult forms.

This is the first year the scientists have managed to breed D. sinicus in the lab. They thought they had succeeded the year before, but all the wasp larvae turned out to be males, which develop from unfertilized eggs—a sign that their mothers never mated. This time, the researchers convinced the wasps to mate by sending them on honeymoons in a sunny greenhouse, confining males and females together in small vials with nothing else to do.

The researchers are still years away from learning how much risk the Dryinus wasps pose to native species. In the end, the choice of whether to release Dryinus or Anastatus wasps may still be fraught with uncertainty.

Over Zoom, I show the vineyard owner Ben Cody a picture of a cecropia moth, one of the giant silkmoths that Anastatus wasps attack. He is silent as he takes in the massive, red-patterned wings. There are more important things than wine, he says. If it came down to it, he would give up his vineyard rather than see a wasp released that would harm native species.

But he worries about people in California, where researchers predict spotted lanternflies will one day spread. California’s climate is among the best in the country for spotted lanternflies, and its grape industry is vast, with $5.4 billion worth of grapes produced in 2022. Those vineyards provide jobs to people who urgently need them.

“A lot of those people came here because the place they were wasn’t safe to live. And, like, what’s their alternative?” Says Cody. “Are those people more important than a moth? Yeah. Yeah, they are.”

The scientists also struggle to balance conflicting concerns. But they agree on one thing: Even if no wasps are ever released, the research hasn’t been in vain.

If it weren’t for the spotted lanternfly biocontrol project, Hagerty would never have uncovered the life cycle of our native Poblicia lanternflies. In California, Mark Hoddle’s colleague Douglas Yanega, PhD, has written a paper describing 15 new species of lanternflies from the U.S. and Latin America. Yanega has known for about 17 years that there were unnamed lanternflies in Arizona, but he had no funding to study them until Americans faced a foreign lanternfly they wanted to kill. “This is the ironic benefit of these invasions, because it has driven all this research into groups of insects that never would have been studied [otherwise]. And this happens every time,” says Hoddle.

Lanternflies are one of many groups of animals that remain virtually unknown in our own backyards, says Yanega. It baffles him. If NASA discovered a distant planet that was home to 10 million life-forms, we’d stop at nothing to learn about them.

“We live on a planet right now that has 10 million undescribed life-forms on it, and nobody seems to give a shit,” he says. “I wish I could show them to everyone.”