If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

The Ultimate Guide to Surviving Tick Season in Pennsylvania

How to check for ticks, what to do if you get bitten, and how to navigate symptoms of Lyme disease

Get wellness tips, workout trends, healthy eating, and more delivered right to your inbox with our Be Well newsletter.

Tick-borne diseases, particularly Lyme disease, are a major problem in Pennsylvania. Here’s what you need to know about protecting yourself. / Photograph via Getty Images

Now that it’s officially summer, you might be spending a lot more time outdoors — whether you’re camping, glamping, biking, hiking, picnicking, or what have you.

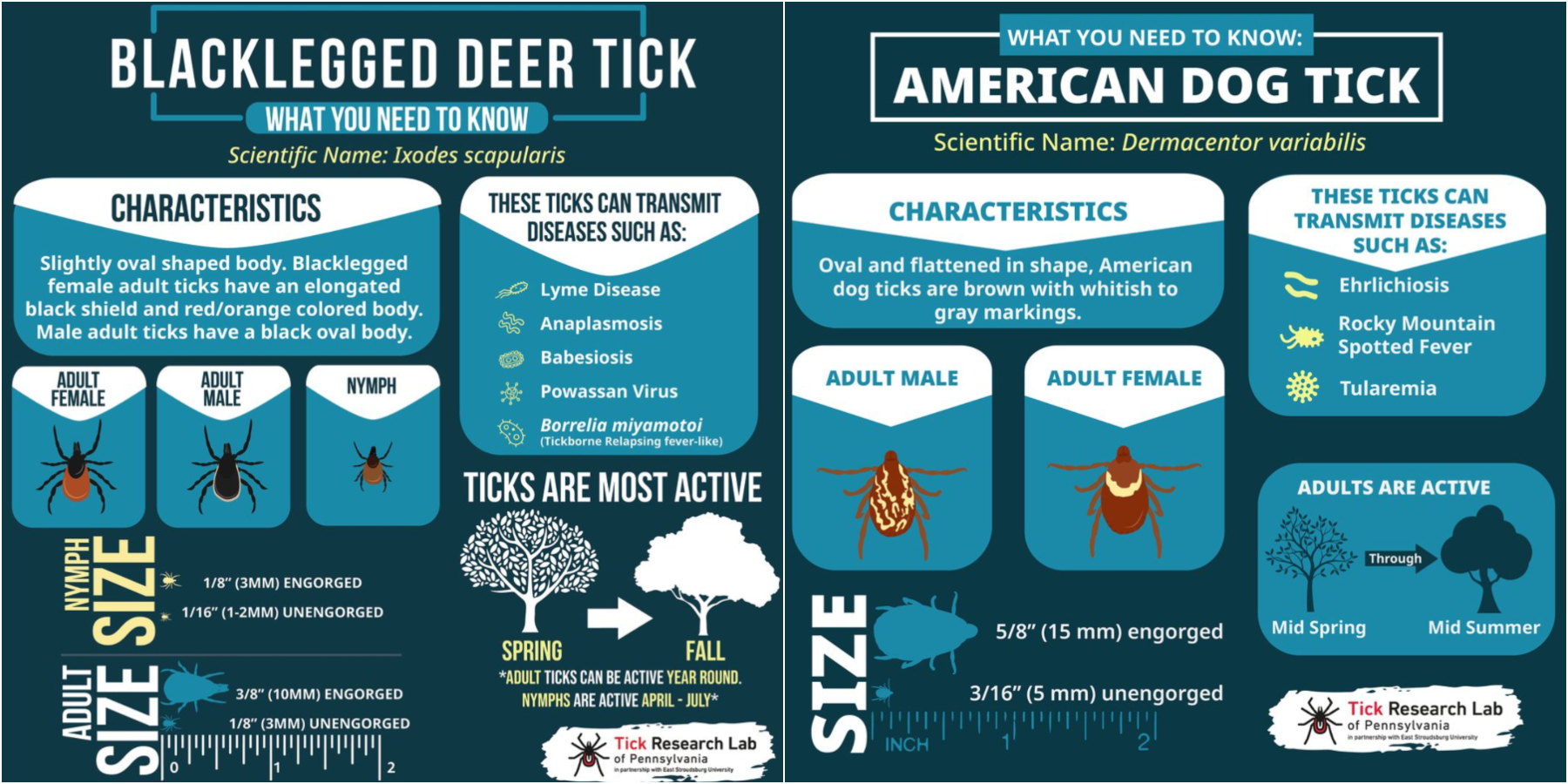

Unfortunately, the warm temps during this time of year cause blacklegged ticks (a.k.a. deer ticks) and American dog ticks to be most active in Pennsylvania. That’s a problem because tick bites come with the risk of illness, including Lyme disease, which can lead to serious health problems.

To help keep you safe from those tiny, but powerful arachnids in the great outdoors, we talked to local pros about how to check for ticks, what to do if you get a tick bite, and how you’ll likely be treated if a doc thinks you have Lyme disease.

Why it matters

Nymph blacklegged ticks are considered to be the most dangerous for transmission of tick-borne illnesses, including Lyme disease, due to their minuscule size. (They’re about the size of a poppy seed!)

This is a serious issue, especially because the Commonwealth has had the highest number of Lyme disease cases in the United States for 10 of the past 11 years. (Ticks and Lyme disease are present in all 67 Pennsylvania counties, FYI.) Reforestation efforts and climate change are likely to blame, according to Penn State scientists who analyzed 117 years’ worth of specimens and data in 2019.

“We have changed the ecology,” says Garth Ehrlich, a microbiology and immunology professor at Drexel University. “We have almost no predators left — no wolves, no coyotes, no bobcats, no pumas. So the white-footed mouse, which is the primary reservoir [of the bacterium that causes Lyme disease], has exploded. And the tick population has exploded to feed on the white-footed mouse. This is coupled with the enormous warming of our region; usually, a lot of ticks would die during the winter, but now most of them survive, so they’ve been able to move into places they’ve never lived before and expand their territory.”

And now, the first tick-centered study of its kind is underway, thanks to the PA Tick Research Lab, which is based at East Stroudsburg University and partially funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Health. (Fun — and useful — fact: If you’ve been bitten by a tick, you can send the pesky creature to the lab and the team will test it for related diseases.) The lab is “analyzing data from 30,000 tick exposures in Pennsylvania from 2019-2021” and the study, whose findings are expected to be released this summer, is “building prediction models designed to help reduce human exposure to ticks, and therefore lower future Lyme disease rates,” according to StateImpact Pennsylvania.

Prevention

What do ticks look like?

According to Penn State’s department of entomology, two tick species — the blacklegged tick (also known as the deer tick) and the American dog tick — account for more than 90 percent of their identification requests, though the lone star tick is also prevalent in Pennsylvania.

The nymphal versions of both species are as small as a poppy seed, while the adults are about the size of a sesame seed. Blacklegged ticks are either black (male) or red/orange (female), and American dog ticks are brown with white or gray markings.

Graphics courtesy of PA Tick Lab

Who’s most likely to be bitten?

Those who are hiking, camping, or doing anything else in forested areas are most likely to be bitten. However, even if you never leave the city limits, you’re at risk, especially if you spend time in parks or in the northwestern or northeastern parts of the city, where there’s more green space.

Pet owners are also more at risk. A 2017 study from the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene found those who owned a dog or a cat were twice as likely to find a tick on themselves. (Note that this study surveyed residents of Connecticut, Maryland, and New York, not Pennsylvania.)

Not all ticks spread Lyme disease, so don’t assume you have it just because you’ve been bitten. However, it’s a great idea to get the tick tested!

How do I prevent tick bites and Lyme disease?

Use insect repellent with a deet concentration of at least 20 percent. (Although deet has gotten a bad rap when it comes to public perception over the years, it’s generally safe and effective as long as you follow the instructions.) For clothing and gear, Dana Perella, Philadelphia Department of Public Health’s acute communicable disease program manager, recommends Permethrin, an EPA-approved spray that repels and sometimes even kills ticks, mosquitoes, and many other insects that come in contact with it for six weeks or six washings after it’s applied.

After you’ve been hiking or park-chilling or really doing anything outdoors, check yourself (and anyone you were with) for ticks before going inside. Ticks like warm, moist areas with thin skin where they can easily attach, so check your armpits, your groin area, the backs of your knees, in your belly button, behind your ears, and under your hairline. You’ll also want to take off the clothes you were wearing and throw them in the dryer on high heat for about 10 minutes — the heat and speed is likely to kill any hangers-on — and shower within two hours of being outside.

Examine your pets if they’ve been out scampering on the trail with you. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends checking for ticks in and around their ears, around their tails and eyelids, under their collars and front legs, and between their back legs and toes.

How do I get rid of a tick?

Even if a tick has attached itself, it takes at least two days for it to transmit Lyme disease, so if you’re able to remove it early (fine-tipped tweezers are the best method), you’re less likely to be infected. Once removed, do not crush it with your fingers or flush it down the toilet. Instead, wrap it tightly in tape or seal it in a plastic bag if you’re sending it off to be tested. Be sure to thoroughly clean your hands and the bite area with soap, rubbing alcohol, or iodine scrub, and disinfect your tweezers!

Symptoms

What symptoms will I develop if I’m bitten by a tick with Lyme disease?

In the early stages, Lyme typically presents as flu-like symptoms — fever, headache, aches and pains — as well as a rash. Some people display the classic bullseye, with dark and light areas, but Abington Hospital infectious disease specialist Joseph Hassey says this trademark pattern doesn’t actually show up all that often. The rash tends to look more like a large red circle and is the size of an orange on average, he says. About 20 percent of people with Lyme disease don’t develop any sort of rash.

If you don’t head to a doctor and get diagnosed at that time, the disease can progress in a variety of ways. Within two to four weeks, you can get Bell’s palsy, during which a nerve weakens and causes one side of your face to droop. Or you can get a heart block, where your heart beats too slowly, producing shortness of breath, weakness, and/or skipped beats and palpitations; meningitis — symptoms include headache, fever, and a stiff neck; pain that originates in your spinal cord and shoots down an arm or a leg; or many of those circular rashes. “Usually at that point, somebody’s going to see their doctor because something’s clearly going on,” Hassey says. “When you’re having terrible pain or breathing problems or cardiac issues, it would be very unusual to not see a medical provider at that stage.”

But, if you don’t have the typical symptoms or if your illness gets misdiagnosed, Lyme could then show up weeks to even a year later as arthritis (typically in a knee), memory lapses, or, again, that shooting pain or meningitis. This has been a major problem with diagnosing the disease: You can get so many different symptoms at different times that simply figuring out you have Lyme can be an uphill battle.

Can’t I just take some kind of blood test to figure it out?

Yes, but there are caveats. The common Lyme disease tests measure your body’s immune system response to the bacterium that causes Lyme, instead of whether the bacterium is in your blood or not. For people who come in with that early rash, this response may not have even started yet, so the blood tests are typically negative. Ehrlich (from Drexel) also notes that the tests were developed using the strain of the bacterium that was common in the 1970s, and folks can be infected with a variety of different strains now. Plus, he says, blood isn’t the best place to look for the bacterium because it can move into the skin, joints, and nerves. Whole-body imaging tests for Lyme are in development, but they’re not widely available yet.

Treatment

So, if I’m diagnosed with Lyme disease, how do I get better?

If you’re in the early stages of the disease — with the rash, fever, aches, and pains — you’ll likely receive 10 to 14 days of antibiotics. Hassey says the chance of curing the condition if you’re treated appropriately then is 95 percent. If Lyme is further along, doctors might turn to several weeks worth of antibiotics or IV versions.

What if I’ve been told I don’t have Lyme disease but continue to have what I think are Lyme-related symptoms?

Don’t assume it’s Lyme. “I always tell patients that if you put everything into the Lyme basket, you’re going to miss other things,” says Marina Makous, a doctor who runs a private practice in Exton and treats a significant portion of patients with suspected or diagnosed Lyme disease. “If you only have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. While we have to be vigilant and think about it, we also have to be mindful that even people with Lyme can get other illnesses.” For instance, ticks can also pass along babesiosis, a malaria-like disease, or anaplasmosis, which can present with similar symptoms to Lyme disease, like fever and chills.

What if I have been treated for Lyme but continue to have what I think are Lyme-related symptoms?

Some people do deal with joint pain, sleep disruptions, or other residual effects of the Lyme infection. “I have to explain to people that Lyme infection could be compared to a hurricane,” Makous says. “Even after the hurricane passes, you still have to rebuild all the infrastructure and fix the bridges and the roads and the roofs.” Antibiotics aren’t necessarily the right approach to these issues. (Cue the controversy around Lyme disease; there’s a good summary here.) As always, you should consult your doctor and come up with a treatment plan that works for you.

This guide has been updated since originally publishing.