Less dust from the Sahara Desert in the past week opened the door to a burst of tropical activity in the Atlantic Ocean, raising hurricane risks as we move into the busiest part of storm season.

Enormous clouds of Saharan dust typically float into the trade winds off West Africa in early summer, smothering potential storms like blankets on fires. That’s what happened in July through mid-August, which helped keep the tropics quiet.

But then "the dust shut off," said Gregory Jenkins, a Penn State University climate researcher.

Now, he's seeing a train of waves cross West Africa into the Atlantic near the Cape Verde Islands, where many of our worst hurricanes form. With less dry and dusty air, "it's just a matter of time before those waves start developing into tropical storms. And that time might be now," Jenkins said.

Desert dunes cast shadows around sunset in Lompoul, Senegal, on April 30, 2023. The small Senegalese desert is about 250 kilometers, or 155 miles, south of the Sahara. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

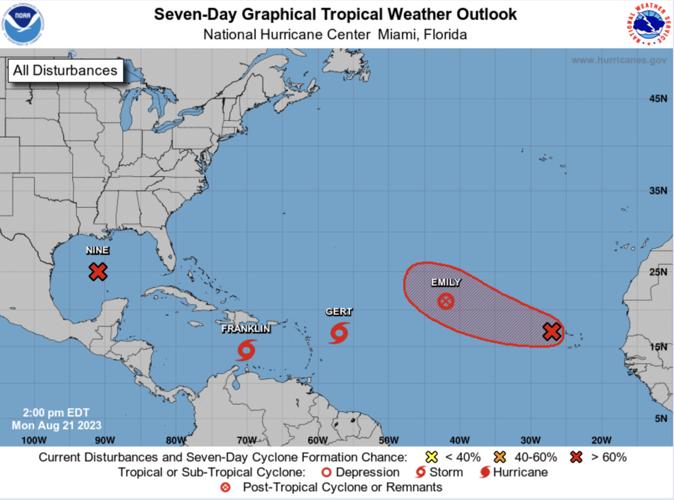

Three named storms were spinning in the Atlantic and Caribbean the afternoon of Aug. 21: Emily, Franklin and Gert. A fourth in the Gulf of Mexico was poised to become Harold.

None are expected to threaten the South Carolina coast, said Emily McGraw, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Charleston.

But the sudden increase in activity jibes with the National Weather Service's new prediction that this year's hurricane season will have more storms than average. Earlier, scientists predicted a developing El Niño would tamp down storms in the Atlantic. Then ocean temperatures spiked.

Dust from the Sahara also plays a leading role in how the hurricane season evolves, a fact highlighted in The Post and Courier's recent "Saharan Connection" project.

In May and June, Saharan dust was unusually sparse, allowing more sun to heat the Atlantic. Two tropical storms, Arlene and Bert, soon popped up. They were among the earliest on record.

"Then the dust came back in July," said Jenkins, who is collaborating with West African scientists on research into Saharan dust. For weeks, a layer of dust stretched from West Africa to the Caribbean. The tropics settled, as the dry and dusty air prevented storms from gaining momentum.

Gregory Jenkins (left) of Penn State and Moussa Gueye are pictured during Jenkins' visit to Senegal in 2023. Provided

But West Africa is now seeing strong rains, which suppresses the dust. "It's raining over the desert in Mauritania," Jenkins said. "And if you're seeing moisture that deep into the continent, that tells you there's going to be less dry air" moving into the Atlantic.

Those same waves of storms can spin into hurricanes when they reach the warm waters around Cape Verde. And late Monday, storms that triggered flooding in Senegal moved into the Cape Verde hurricane cauldron. Satellite maps show rotation. The National Hurricane Center says the swirling mass has a 70 percent chance of developing into a tropical storm during the next seven days.

If that happens, we could soon be up to the letter "I" (Idalia) in the center's named storm list, with the most active part of the season — early September — still to come.