In a commonwealth with a long history of mining, Penn State’s Department of Energy and Mineral Engineering is focusing on refining mining to be more environmentally sustainable — as mining engineering faculty say mining will play a large role in a sustainable future.

Barbara Arnold, a professor of practice in mining engineering at Penn State, said mining is a factor in many types of expanding forms of renewable energy, including solar, wind, hydro, tidal and geothermal.

Arnold said while many of Pennsylvania’s mines from the 1700s, 1800s and early 1900s have been closed, their wastes, also known as tailings, were left behind.

A tailing is a term for mining waste, unusable material surrounding valuable minerals. Some common mining causes of environmental damage have been tailing ponds that have broken and flooded certain areas, according to Arnold.

Arnold said one of her future students will study the “beneficial use” of tailings.

“Can we make those into bricks? Can we add those to concrete? Can we make pottery or tile or something like that out of those tailings?” Arnold said.

A core emphasis of modern mining is “reclaiming” mines once they have expired, according to Arnold.

“You can't build a new mine without knowing how you're going to reclaim it in the end,” Arnold said.

Reclaiming a mine usually means returning the land of an expired mine back to its original state, according to Arnold.

For example, if a large hole is dug for an open-pit mine, then the tailings can be placed back in the hole to refill it, Arnold said. Since the tailings expand during mining, fitting them into the hole to match the “contour” of the surrounding land can be a challenge.

Some reclaimed mines can even be transformed into recreation areas, according to Arnold.

During the World Wars, eastern Pennsylvania’s anthracite mines provided much of the coal to power the U.S. Navy, but Arnold said the U.S. government didn’t regulate the closing of the mines.

“The government said, ‘Don't worry about putting this stuff back the way it should be put back. We just need the coal,’” Arnold said.

MORE NEWS COVERAGE

Planet Fitness will open an additional location in downtown State College in the Fraser Cent…

Many of these coal mines are now being reclaimed, often being developed into golf courses and housing developments.

Mohammad Rezaee, an assistant professor of mining engineering, said he’s involved in projects where the goal is to process tailings to extract “critical elements and valuables,” as well as refine the remaining material to be “environmentally benign.”

Rezaee said acid mine drainage is a particular issue he’s focused on. Acid mine drainage is waste from coal and sulfide minerals, he said.

The mineral pyrite is a byproduct of processing coal and sulfide minerals, Rezaee said. When pyrite is oxidized, it can produce acidic chemicals, which can “dissolve minerals or elements within the host rocks.”

When combined with water, these chemicals are “highly electrically conductive” and are an environmental concern, Rezaee said.

According to Rezaee, federal law requires acid mine drainage to be treated before being exposed to the environment.

Rezaee said he and his colleagues are developing methods to treat acid mine drainage — so valuable elements can be retrieved.

Younes Shekarian, a graduate student of energy and mineral engineering and a research assistant at Penn State, said he’s researching how to recover those valuable elements, such as cobalt and manganese, from “secondary resources,” including acid mine drainage.

Manganese is mainly used in stainless steel production, and Shekarian (graduate-mineral processing) said America is 100% dependent on manganese imports.

“We need this element,” Shekarian said.

Shekarian said Pennsylvania currently produces the third-highest level of coal in the United States.

Much of the acid mine drainage present in Pennsylvania is due to the abandonment of many coal mines over the years, according to Shekarian.

Shekarian said treating acid mine drainage costs money, but by recovering elements such as cobalt and manganese from the drainage, the process might actually become profitable.

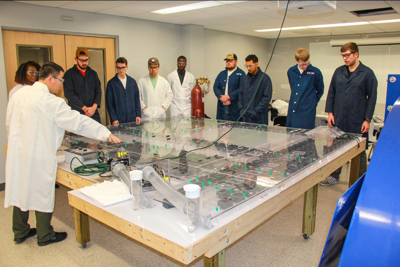

Mining and Mineral Processing graduate students, Younes Shekharian and Behzad Vaziri Hassas, recover iron, aluminum, rare earth elements, cobalt and manganese from acid mine drainage.

“When we recover some type of cobalt or manganese, it means that we can return some of this money, we can make profit from this project,” Shekarian said. “Total cost of treatment of [acid mine drainage] will be decreased.”

Shekarian said he’s hoping to use ozone in the process of treating acid mine drainage.

However, there are not many “primary resources” of manganese currently available, according to Shekarian.

Arnold said Pennsylvania currently has operative limestone and coal mines, as well as aggregate, sand and gravel mines used for concrete production.

The coal mined in Pennsylvania is used for a variety of purposes — including metallurgy, or steelmaking, Arnold said. Anthracite coal is also used for electrodes for aluminum smelting, and the fine anthracite goes into water filtration.

Some Penn State mining faculty are working to turn anthracite into graphene, which Arnold said “adds a lot of strength to whatever you put it in.”

Meeting the demand for copper, which Arnold said will increase in the near future mainly due to the electrification of energy, will become one of the mining industry’s most imposing challenges.

“Because all the copper is deployed, it's not as if there's going to be a lot of copper to recycle,” Arnold said.

MORE NEWS COVERAGE

The State College Police Department requested the public's assistance Tuesday in identifying…

Sekhar Bhattacharyya, chair of the mining engineering program at Penn State, said electric vehicles require much more copper than gas vehicles.

Arnold said one wind turbine needs 4.7 tons of copper, and the mining industry will need more mining engineers in the future to mine the copper, along with all the other minerals modern society relies on.

“Unless [mining engineering students] come through the doors here and at the other programs around the country, we're not going to have enough mining engineers to actually go in and do this safely and in an environmentally friendly way,” Arnold said.

The mining industry will also need people with other expertises, such as mechanical and electrical engineering, as well as computer science and chemistry, Bhattacharyya said. The mining program is also considering offering a minor.

“If we are saying, ‘Mining engineers are going to do all of this,’ that’s not a correct statement,” Bhattacharyya said.

Bhattacharyya said mining around the world could be performed in a safer manner. For example, cobalt, a mineral primarily used in batteries for electric vehicles, is found in the Congo region of Africa, and Arnold said cobalt safety is a big issue because cobalt dust is toxic if inhaled.

Many local Africans resort to artisanal mining without any safety precautions, according to Bhattacharyya.

“If there are other countries and other people with stable governments, they need to come in and help [the artisanal miners] in doing it correctly so that you neither destroy the resource nor kill each other,” Bhattacharyya said.

At Penn State, there’s been a focus on sustainability and reclamation for as long as Arnold said she can remember.

“We can't leave some of the blemishes on the earth that mining has done in the past,” Arnold said. “We can't do that anymore.”