In much of the country, deer hunter numbers are on a long decline. Pair that with a lack of natural predators and you get whitetail population booms, leading to the need for new tactics to manage deer populations.

This is particularly an issue in the Northeast. With millions in damages caused by whitetail deer, states like New Jersey are dealing with a real deer population problem. Just 27 farmers saw $1.3 million in damages, according to a report by Rutgers Cooperative Extension and the Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station.

High Deer Densities and Low Hunter Numbers

The state has a deer density estimated range of 60 to 239 deer per square mile, according to a study by Steward Green for the New Jersey Farm Bureau. The recommended deer density should be between 10 to 15 deer per square mile. This kind of population density makes deer management extremely difficult.

Wildlife officials and the authors of the Rutgers report said that leaning on the state’s available hunters won’t even come close to solving the problem. Why not? Partly because there are too few hunters. Less than one percent of New Jersey’s population holds a hunting license.

The low number of hunters in New Jersey means even if the state wildlife agency were to allow hunters to take more bucks per season, for example, the impact likely wouldn’t be enough to make a dent. (And the state already has liberal bag limits for antlerless deer.) That’s why officials are looking at non-lethal options like fencing and sterilization, but those solutions are costly.

New Jersey isn’t the only state with wildlife management issues. Vermont has also noted strained deer habitat due to overpopulation in certain areas. This is causing the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department to rethink management practices, including focusing hunting efforts on antlerless deer.

Washington D.C. and surrounding areas, like Arlington, Virginia, are also experiencing overpopulations of deer. In many of these areas, tackling the problem with hunting alone is tough because excessive development means there aren’t many obvious places to hunt. Serious suburban hunters are effective at taking deer all year long, but there’s a limited number of bowhunters who have mastered suburban tactics, regulations, and the art of asking homeowners for permission to shoot their deer.

A Long-Term Problem

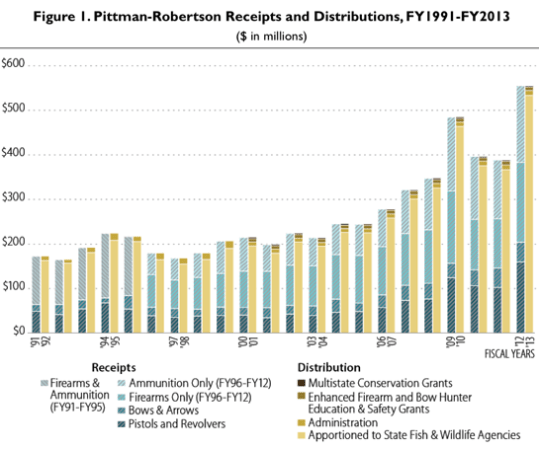

With many wildlife management and conservation programs getting between 60 to 80 percent of funding from hunters, finding the money for new management programs could prove to be difficult as fewer hunters pay for licenses. Duane Diefenbach, a leading whitetail deer researcher and professor of wildlife ecology at Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences, says he doesn’t see this decline in hunters changing anytime soon.

“It’s been happening for 20 years,” says Diefenbach. “We’re just getting to the point that some states are really going to struggle to use recreational deer hunters as a management tool.”

Hunting participation peaked in the 1980s with nearly 17 million hunters purchasing licenses. There was a recent uptick in hunting participation during the COVID-19 pandemic with an overall hunting license increase of about five percent in 2020, according to the Council to Advance Hunting and Shooting Sports.

But these national hunter numbers—if they’re truly accurate—don’t address localized issues like what’s happening in New Jersey, Vermont, and Virginia. Right now many states across the U.S. still have plenty of hunters, in fact there’s more and more interest and pressure on Western big game hunting. But those same hunters putting in for Western big-game draws aren’t exactly interested in traveling to the New Jersey suburbs to deer hunt.

Plus, America’s deer hunters are getting older. The simple fact of the matter is that baby boomer hunters, which make up a huge portion of America’s hunters, are aging out and there aren’t enough new hunters to replace them.

The Impacts on Deer Management

The future of whitetail deer management might look different than it does today. And the changes have started with how hunters are allowed to take game and how many tags are issued.

Diefenbach noted adjusting current hunting regulations could be a big part of the solution. He pointed to two different successful programs: Earn-a-Buck and Earn-a-Second-Buck. Both prioritize shooting does to help control populations with key differences. Under Earn-a-Buck rules, you must kill an antlerless deer before killing a buck.

Under Earn-a-Second-Buck, if you kill an antlerless deer you can then kill two bucks, or if you kill a buck first, you’ll have to kill an antlerless deer before you can take another buck.

“That has been very successful for Virginia, and they’ve been able to increase the harvest of antlerless deer which allows them to better manage the deer population.”

These regulations are controversial with many hunters who are only interested in killing one deer. But they’re not as controversial as other methods for managing populations like fencing, sterilization, and sharpshooting. While these control methods can have some success, they are typically expensive.

“Why have state agencies relied on recreational hunting for so long? It’s because it’s the most cost-effective way to manage a deer herd,” says Diefenbach.

Diefenbach also pointed to the possible commercialization of deer meat as an option. This is something that’s been done in other countries like the UK. Right now it’s against federal law for a hunter to sell their deer meat.

While you can find venison at specialty shops and high-end restaurants, it’s all imported or from farms. Right now, venison is at an odd place in America’s food scene. It’s either in the freezer or on the table of hunters and their families, in high-end restaurants that pay the specialty shops for the meat, or at the local food pantry via donations from hunters or wildlife agencies. You won’t find it at the local supermarket or middle-of-the-road restaurant.

“A lot of laws and regulations would have to change,” says Diefenbach. He added that changing those regulations is something that could be largely handled at the state level. “For non-migratory animals like whitetail deer, there’s [little] federal oversight.”

There is at least some precedent for modern market hunting in America. Last summer, Outdoor Life reported on market hunters in Hawaii harvesting overpopulated free-ranging axis deer on Molokai Island.

Additionally, new revenue generators for wildlife agencies could be the answer. With fewer hunters and fewer licenses being sold, taxing other parts of society might be necessary. States have passed taxes on real-estate transfer fees, lottery ticket sales, license plate proceeds, and more. Missouri, for example, enjoys a conservation sales tax: For every $8 spent on taxable items, one penny goes to conservation. That tax adds up to the bulk of the Missouri Department of Conservation’s annual budget, earning $133.7 million for the state agency in 2021. In comparison, permit sales brought in $41.5 million last year.

Read Next: Is it Time to Rethink the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation?

These kinds of conservation taxes put the burden of supporting wildlife management on all citizens as opposed to primarily relying on hunters and anglers. With wildlife management impacting all aspects of society, these taxes make sense in many cases.

Interestingly, Recovering America’s Wildlife Act could be part of the answer. This federal act would provide $1.4 billion to states and tribes to help manage animal populations. The projects are funded on an as-needed basis determined by state fish and wildlife agencies and ultimately the Act is meant to help prevent imperiled species from hitting the Endangered Species List. But if deer were damaging habitat that was important to a more fragile species, it’d be potentially feasible for a state to get funding for management efforts.

The high concentration of whitetail deer in certain parts of the country like New Jersey may seem like a small, local issue in need of a solution targeted specifically at that single issue, but in reality, it’s a highly complex issue with far-reaching implications.