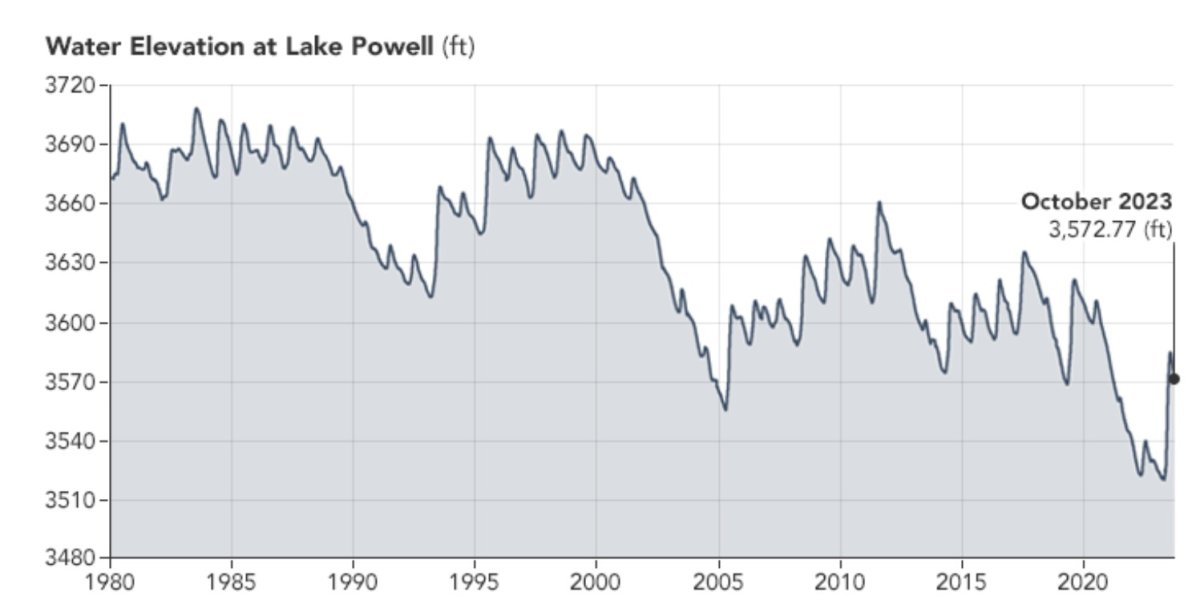

Lake Powell has seen its water levels creep back upwards since this time last year thanks to the above-average snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains over the spring and summer.

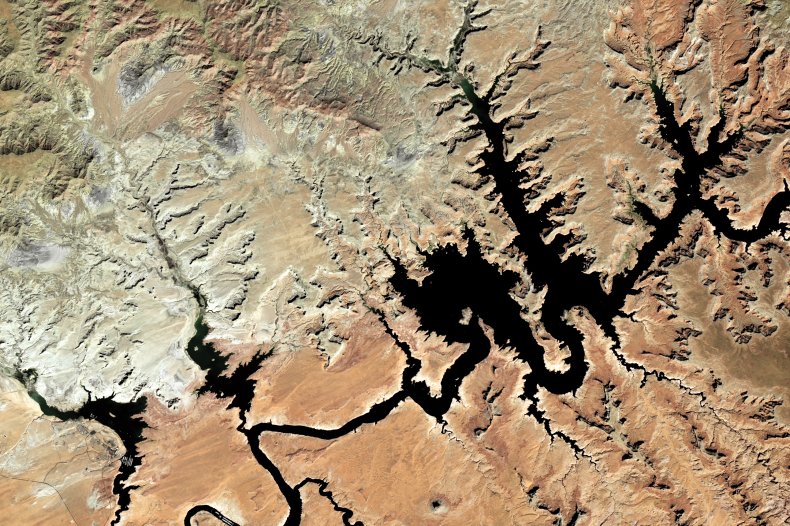

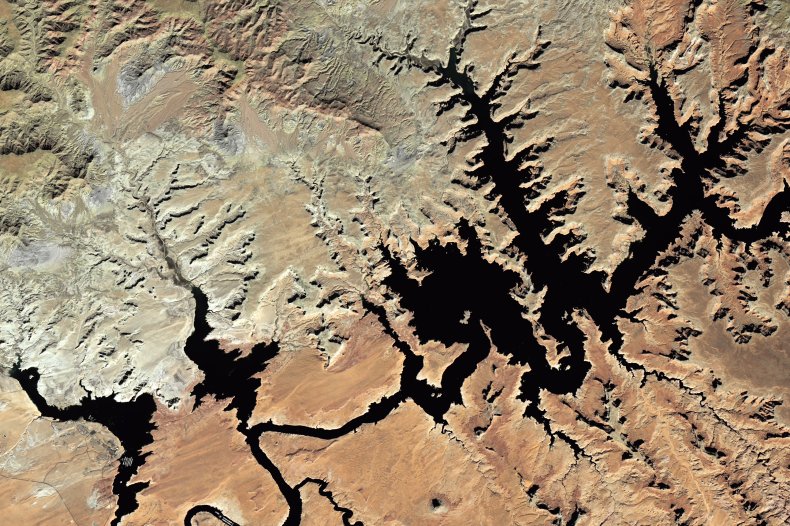

The differing shorelines of the reservoir between September 23, 2022, and October 20, 2023, can be seen in satellite images taken by the OLI-2 (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 9 and the OLI on Landsat 8, respectively.

Lake Powell sits on the Colorado River at the Utah and Arizona border, formed by the Glen Canyon Dam. The second-largest reservoir in the U.S. after Lake Mead, it has been slowly drying up due to the megadrought that has plagued the U.S. southwest for the past two decades or so, reaching record lows in April this year at only 22 percent of its full capacity.

However, thanks to the huge snowpack that accumulated over the winter, the lake saw a significant water level rise as the snowmelt ran down the Rockies. While on November 16 last year, the lake's water levels stood at 3,529.12 feet above sea level, as of November 14, 2023, the water lies at 3,572.18 feet, making it 35.7 percent full.

On September 26, 2022, three days after the first satellite pictures was taken, the lake level stood at 3,529.64 feet, while on October 20, 2023, during the second satellite picture, the levels were 3,572.93 feet.

Even with the plentiful water this year, the southwestern states aren't entirely clear of drought, and several years like this would be needed to pull Lake Powell closer to its full capacity.

"It's not easy to say what it will take to get us out of a drought situation, but even if conditions suddenly change and become wetter, it will take a long time for the Colorado River Basin to completely recover and refill its reservoirs," Antonia Hadjimichael, an assistant professor in geosciences at Penn State University, told Newsweek.

There are fears that the drought could eventually cause Lake Powell to run dry, falling below the "minimum power pool" level of 3,490 feet, where water can no longer flow through the hydroelectric turbines that generate the Glen Canyon Dam's electricity. A draft "Environmental Impact Statement for Colorado River Operations" released by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in April predicted that water levels have a 57 percent chance of dropping to this point before 2026, though this was revised in October to an 8 percent chance, as a result of this summer's water level rises.

The effects of climate change may yet worsen the megadrought in the southwest, further drying out Lake Powell in the years to come.

"Unfortunately, climate change is exacerbating this issue, causes less snowmelt and warming conditions that increase demand for water by soil and plants," Erica Smithwick, a professor of geography at Penn State, told Newsweek. "A recent study showed that 42 percent of the last two decades' dry and hot conditions can be attributed to climate change."

This drying of reservoirs along the Colorado River could be disastrous for residents of the nearby states, as Powell alone provides water and electrical power to 40 million people around the southwest, including in Las Vegas, Phoenix, Los Angeles and San Diego, as well as agricultural water to between 4 million and 5 million acres of nearby farmland.

"Agriculture is the largest user of Colorado River water so it is experiencing the bulk of the impacts," Hadjimichael said. "Farmers and ranchers are now in a world where there is less water available to irrigate their lands and sustain production. Impacts on agriculture will also have second-hand consequences for the rest of the country and other regions that depend on grain and vegetable exports from the southwest."

To combat some of these issues, it has been suggested to drain Lake Powell to refill Lake Mead, a move known as "Fill Mead First." That is being pushed by some organizations including the Glen Canyon Institute. This plan has been met with backlash, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation hasn't indicated that it's considering the move.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about droughts? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.